What I Learned from Writing 70 Newsletter Posts in One Year

A retrospective on the first year of CHANGING LANES

One year ago, on September 3, 2024, I began Changing Lanes. My inaugural piece was Tesla Isn't Going to Succeed in Robotaxis; my latest was Robotaxis Have a Bullying Problem. In between, I wrote 70 posts, publishing one long article, averaging 2,700 words, each Tuesday… and, for more than six months, an additional link roundup piece on Thursdays. Today, I have a 1,000+ free subscriber list and a healthy subset of paid subscribers.

Today, I want to share what I’ve learned: about writing a newsletter, to short deadlines, on the Substack platform. After that, I’ll add some reflections about Substack Notes, the Roots of Progress Institute, my forthcoming speaking appearances, and finally, the new professional chapter of my life that begins today.

The Consistency Premium

The most important thing I’ve learned is not glamorous. It is that consistency wins.

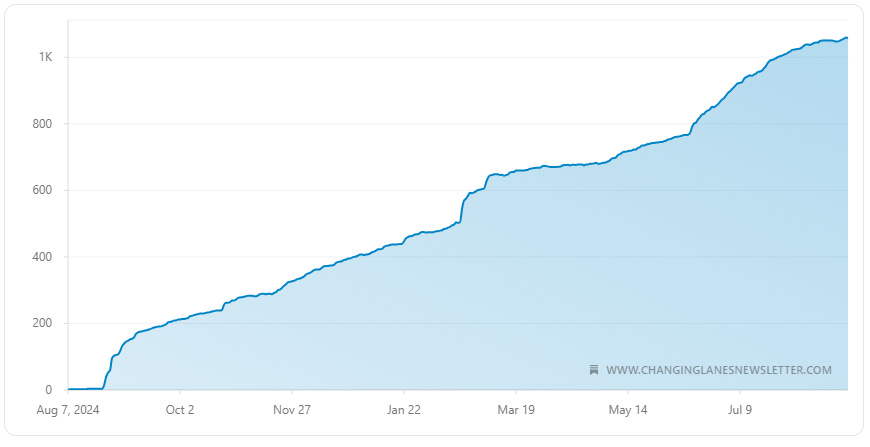

This graph showing my subscriber count over the past year.

As the graph shows, I picked up 100 subscribers initially thanks to pre-launch marketing to friends and professional contacts. Since that time, though, my numbers have slowly risen, and at a regular pace, barring a discontinuous jump in growth in mid-February, and subsequent reversion to the mean till June. I’ll talk about what those discontinuities wore in a moment, but for now, I want to focus on the big picture, which is linear return to effort.

Look at the graph more closely. It’s not a smooth line: there are tiny divots throughout. Each of those divots represents a publication day. They are divots because, paradoxically, every time I published a new piece, I immediately lost subscribers: because the piece showing up in their e-mail inbox annoyed them, or bored them, or simply reminded them of my existence.

At the same time, though, in the days following, each piece also brought in new subscribers, more than the number that departed. Amazingly—suspiciously?—the content of that piece doesn’t seem to matter; just the fact of it. Whether a week's post generated heat or landed with a thud, approximately the same number of new readers joined. (Again, with one notable exception.)

The lesson to take from this is that there is that, over time, consistent output wins.

There are several reasons this is so.

Readers develop preferences for things they encounter frequently. I write Changing Lanes with a particular voice, tone, style, and perspective. The more readers encounter my writing, the more familiar this package becomes, and for those who like it, the more they form a taste for it.

The algorithm develops preferences too. I have no insight into how Substack works, but it seems likely that the platform shows my work to more potential readers because my work appears on it more frequently: the algorithm recognizes that I am prolific and broadcasts my work more often and more widely as a result.

Finally, I, the writer, get better too. Writing is like any other skill, or muscle: the more one practices it, the better one gets. Finding the discipline, every week, to find a topic worth writing about, finding something to say about that topic, and putting it into words in as engaging a fashion as I can, was difficult to begin with. It hasn’t become easy, but it’s certainly become easier.

So the first thing I’ve learned is that success on Substack is like success everywhere else: 80% of it is showing up.

The other 20% of success is, having shown up at the table, putting the right things down on it.

Vegetables in Sauce

The least surprising thing I’ve learned writing this newsletter is the pieces that get the most views are, generally, also the pieces that generate the most subscriptions. I wish I had found the opposite, so I could name my own paradox and present it as a counter-intuitive finding, but no: the more views, the more subscriptions.

If you were to track the ten posts of mine that generated the most views, and the ten that generated the most subscriptions, you would find seven pieces on both lists: my seven most popular pieces. For the record, those are:

· Book Review: Tyler Cowen’s Stubborn Attachments

· Love-Hate Relationships with High-Speed Rail, Waymo, and Electric Cars

· Canada Shouldn’t Build High-Speed Rail

· Public Transit Should Not Be Free

Leave aside the book review, as it’s anomalous: Tyler Cowen, the Blogfather, made positive note of it on Marginal Revolution and for a brief second the MR spotlight was on me, for which I am grateful! And leave aside the second item, an Off-Ramps link round-up from June, which is also anomalous in that I can’t account for why it succeeded so much more than its siblings (sometimes lightning strikes).

The rest of the list are what I will call Vegetables in Sauce.

They’re vegetables because they are deep dives: like most of my work, about 2,800 words long. They strive to be grounded, to lay out the argument clearly, and support it with evidence. They are, I hope, intellectually respectable contributions to the discourse.

But while steamed vegetables are healthy, they’re rarely devoured with gusto. Adding sauce to them makes them delicious. And these articles have sauce, by which I mean that each one makes a strong claim. These pieces don’t simply report the facts and let the reader decide; they aim to persuade the reader to take a particular view of a matter. Other examples that don’t fall in the top ten but still performed strongly include Don’t Privatize Amtrak; Cars Need Buttons, Not Touchscreens; and (sigh) The United States Should Not Annex Canada.

Looking over the list, I’m faintly disappointed that so much of my work, and my successful work also, is negative: not what we should do, but what we shouldn’t. I want to be constructive, to explain how we should proceed. But, in this fallen world, arguing that Good Idea Is Good is offering a vegetable without sauce. Taking a stand against conventional wisdom is the sauce, the ‘man bites dog’ angle; actually believing the case, and bringing evidence, is the vegetable. Vegetables alone don’t get read, while sauce alone is mindless contrarianism.

The best posts of mine, it seems to me, have both.

The most successful posts also have both, but more besides. Exploring briefly why these posts did so well is useful to understanding what makes a newsletter succeed. To wit:

One is The Case for Fare Enforcement, in which I argued that transit agencies should make the capital and operational investments necessary to ensure that every patron pays their fare. This is, on views, the third-most popular thing I have written, and I have to confess that I found that out well after the fact. I didn’t think when writing it that it was going to outperform my typical post… which it did, by a factor of five. My first thought was that this succeeded because it channeled the frustration of thousands of transit users who think their transit agencies are getting it wrong: in other words, a classic ‘he’s saying what we’re all thinking’! reaction.

But on second thought, I concluded that it was the framing that mattered. I open that piece by stating that, regarding fare-enforcement policy, I had changed my mind. Making that statement (not an admission, a statement) on why I formerly believed one thing but came to believe another earned some attention on Rationalist Twitter. Let the record show that changing your mind, and being open and honest about the reasons why, is not only good intellectual hygiene, but also can appeal to an audience: it’s a costly signal that you are committed to getting things right.

I mentioned earlier that, looking at my subscription rates, only one post is visible there. That is Canada Shouldn't Build High-Speed Rail, my second-most read piece, and easily my best subscription-getter, which attracted more new subscribers than the next three highest subscription-getters combined.

Why did it pull that off? For a few reasons, I think.

Firstly, it is classic vegetable in sauce: the piece takes a clear, evidence-based position against popular sentiment. As I open the piece by noting, high-speed rail (HSR) is popular among educated North American liberals, and opposing it risks looking backward, ideological, or mindlessly contrarian. But there was and is good reason to think this project should not be pursued in its current form.

Secondly, it was very timely. I advise anyone who wants to write on Substack to read Nate Silver’s advice on the subject, and especially this section:

The equivalent in the newsletter business is when there’s a topic that you have some unique expertise or insight on — and you’re at bat when the news comes in and prepared to take a big swing. The most popular post in Silver Bulletin history… is this one on Ann Selzer’s Iowa poll that — dubiously and wrongly! — had Kamala Harris leading in Iowa. That post came out relatively late on a Saturday evening, usually one of the worst times for newsletter traffic. But it got almost 350,000 views that night and an equal number the next day. I canceled my evening plans to turn it around as quickly as I could. I’m glad I did because it would have been an expensive night out, considering the opportunity cost [emphases added].

As I recall, the public announcement of this HSR project came out on Wednesday. I had my Thursday piece ready to go, but as soon as I got the word, I realized that this was precisely what Silver was talking about, a high-profile development in a field I knew quite a bit about and consequently held a view at odds with almost everyone. And I remembered the rest of his advice too: I postponed the prepared work and worked in a white heat for the afternoon and evening to research and write 3,000 polished words on why HSR was a bad idea.

The following morning, I got up early and began promoting it on both Substack and Twitter immediately upon its 0700h publication. It got cross-posted on both, in some cases by well-known people, giving it, for a time, a nation-wide profile. The views, and subscribers, followed.

Consider this a second data point in support of Silver’s claim: nothing beats moving fast, or even first, on an important topic where you have expertise.

Sharp-eyed viewers of the graph up top will have noted that after the initial rush of subscribers that this post generated, the rate of acquisition trailed off quite a bit. Those viewers may wonder if the newcomers got a taste of my regular output and departed as quickly as they came. There may be some truth to that; certainly my immediate follow-piece earned me my first-ever hate mail. Unfortunately, the matter is confounded by the fact that shortly after that post, I also began to give notice of Changing Lanes’ impending paywall.

Speaking of the paywall: I have no doubt that warning people that it was coming decreased my rate of free-subscriber acquisition. Most newcomers, seeing that note, didn’t know yet if the newsletter was worth paying for, and chose not to stick around for something that they know would shortly cease to be available. But just as the slope tended down while I was warning about the paywall, it tended up once I actually implemented the paywall, and begin charging for some of my content. That, I think, is Substack’s algorithm working for me: the platform is more eager to promote my work when they know promoting it means they’ll get a share of the resulting income.

One lesson to learn here is that if you want to maximize your subscriber base, leave the paywall off as long as possible. And there may be good reasons to do so: one friend of Changing Lanes, whom I will not name, has told me they keep their newsletter free because they want to maximize their impact on the field on which they write: a field of very high policy salience, where wide reach gives the newsletter gigantic real-world influence.

By the same token, if one wants to maximize one’s subscriber base, one might only write vegetables in sauce, and never write jeux d’esprit. While it’s true that my attempts, like this one or that one, have some admirers, I only know this because I have been told so in person; I can’t see it in the numbers.

It may seem then that I’m confessing two crimes: I know that a paywall, and departing from my formula, are both making Changing Lanes less successful than it could be. Should I not then take my own advice, and quit both? By no means. The most important lesson, already foregrounded, is consistency: the way to win this game is to put out work one is proud of, at least once a week. A paywall brings in money, and the occasional flight of fancy brings me joy. If I didn’t have those things, I wouldn’t be able to write as consistently as I do.

So my final advice to an aspiring newsletter writer is to do what it takes to write well, and often. Everything else is downstream from that.

The Now and the Next

In keeping with the lessons I have learned, I want to draw your attention to a few other matters.

I am active on X/Twitter, though almost exclusively to promote my writing. For more robust and free-form posting, I encourage you to follow me on Substack Notes; I post there around twice a day on average. I’m pleased to report that Notes is, slowly but surely, becoming a viable alternative to X, like it was in the old days. If you are looking for a social-media platform to spend time on, it seems to me to be the best one on offer right now.

I have written a few times about how this newsletter came into being thanks to the support of the Roots of Progress Institute’s Blog-Building Intensive Fellowship. One year later, I would be remiss if I didn’t thank the RPI team for their help launching this newsletter, and for maintaining the intellectual community that sustains it. To the extent that this newsletter has been successful, the RPI deserves a big piece of the credit. I’m pleased that I will be able to attend the RPI’s second annual Progress Conference in October 2025; if you will be there, I hope we can connect in person!

Later this week, I’ll join the Canadian Automated Vehicle Initiative (CAVI) to offer a webinar on the Trans-Canada Autonomous Truck Demonstration Project. This is an ambitious initiative for Canada to achieve a milestone in automated trucking by preparing for a driverless truck to travel from Halifax to Vancouver—5,800 km, which would be the longest such trip ever—in 2028. I’ll be discussing the business case, project plans, regulatory challenges, and how this groundbreaking demonstration could position Canada as a global leader in automated trucking while addressing critical driver shortages. If you are interested, please register for free at the CAVI website; click on the Events tab.

That’s a digital talk, but later this month, I’ll be speaking at two conferences in person. The first is the Ontario Transit Funding Forum in Toronto. At the Forum, co-hosted by Transport Futures and Toronto Metropolitan University's TransForm Lab, I’ll join other expert speakers from government, business, academia, and NGOs to discuss revenue and funding policies that can support efficient transit operations while increasing ridership. See the images at the end of this post for more information. You may register here, but note that Transport Futures has generously offered a 10% discount to paying subscribers of Changing Lanes! If that’s you, and you would like to attend, please contact me via Substack for details.

The second is the International Association of Transportation Regulators’ annual conference in Nashville. I’ll be on stage discussing robotaxis, ridehail, and how the right mix of technology and regulation will lead to the best possible outcomes for mobility in North American cities. Tickets are still available, which you may purchase here.

And finally, a professional announcement. I’m pleased to report that, after several months of consulting work, as of today I'm joining Flix, the international intercity-bus-service provider, as the firm’s lead for public policy and government affairs in Canada. In this role, I’ll be helping Flix to achieve its goal of building a truly national, coach-based, intercity transport network. As an advocate for mobility, and for multi-modal transportation, and especially for ensuring everyone can get around without needing to own a private car, Flix’s mission aligns perfectly with my own, and I couldn’t be happier to taking this challenge on.

This won't change the focus or independence of Changing Lanes. I'll continue covering the full spectrum of mobility innovation—from driving automation to transit developments to goods movement—with the same analytical approach, and voice, that you're used to. When I write about topics where my Flix role is relevant, I'll note that connection clearly. But the other side of that coin is that I will write about those topics advisedly: my work at Flix depends on using commercially-sensitive data to develop and implement growth strategies in a competitive market. These are not things to talk about casually in public… so I will not. Further, the newsletter will keep the once-a-week cadence it has had since June; I want to give both my readers and my employers my best effort, and publishing more than once a week would prevent me from following through.

But I will continue to talk about mobility innovation, particularly driving automation, here each week. My book, The End of Driving, will be published in just a few weeks. As I argue there, we are poised to enter a future of transportation that has great potential, for both progress and dystopia. The choices we make in the next few years will echo for decades to come. Here at Changing Lanes, I’ll continue to make the case for the best choices, which will deliver the most good to the most people.

Thank you for sharing this journey with me.

Thank you for sharing so transparently about your journey over the first year of your newsletter. As someone who recently started a Substack newsletter in a related domain (cities and technology), your insights are valuable and appreciated.

Consistency being most important is encouraging, since that's entirely under the writer's control, while things like the algorithm and which posts strike lightening are not. It's also good to hear that Substack Notes are working well and could be a viable X alternative.

I'm enjoying your newsletter and appreciate your in-depth approach while also taking a stance rather than blandly presenting data. Vegetables in sauce, not bad.

Congrats on the new gig! See you at Transport Futures.

Happy anniversary! I’m proud of what you’ve built in the past year. ❤️