Robotaxis Have a Bullying Problem

Dealing with pedestrians’ bad behaviour

Imagine an August afternoon in Phoenix at a sleepy traffic intersection, where the light is about to change. Northbound traffic gets a green light, eastbound pedestrians get a DON’T WALK warning. But one man crosses anyway. He steps into the intersection against the signal, directly in front of a Waymo robotaxi, perfectly identifiable from the spinning LIDAR on its roof.

The Waymo stops instantly.

The man, grinning, continues across at a leisurely pace, phone in one hand, iced coffee in the other. He doesn’t gesture ‘thanks’ or ‘sorry’; he doesn’t acknowledge the Waymo at all, because he doesn’t need to. The vehicle is programmed to protect him, and he knows it.

Since the introduction of the automobile, city streets have operated under a mixed regime of law, custom, and risk.

The law says, cross against traffic and you can get cited. Custom says, cross against traffic but only if it won’t slow anyone down. And risk says, cross against traffic and the cars might stop, or might not. If they do, you can proceed, but you’ll get honked at, or flipped off, or stuck mid-street. But if they don’t, you’ll be hit, which will hurt you if it doesn’t kill you outright.

Driving automation changes the equation. Robotaxis—Waymos or Zooxes and perhaps Teslas—are designed to avoid collisions wherever possible. A robotaxi will always yield, always brake, always err on the side of the pedestrian. That will be great for safety, and a vast improvement on the carnage on our streets today. But it does remove the latent deterrent of danger; and human behavior will adapt.

Phoenix is already seeing edge cases. Pedestrians, cyclists, even other drivers are beginning to learn that an AV will not assert its right of way. The social equilibrium of the street is fragile, and relies on mutual recognition of risk. Remove one party's exposure to that risk, and the counterparty can be exploited. The more people understand this, the more exploitation there will be.

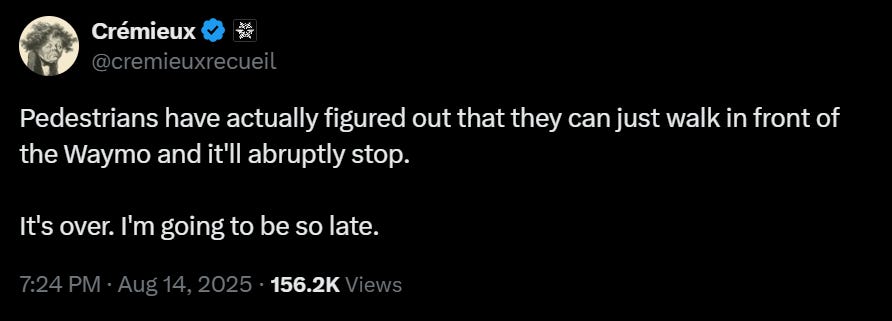

https://x.com/cremieuxrecueil/status/1956134836651089969

This development is concerning. If robotaxis are consistently exploited, and as such deliver suboptimal service, it will have a variety of bad effects. Robotaxi delays will harm the passengers aboard, who will not be able to count on a reliable trip, as well as all other road users, who will have to put up with jerky, stop-and-go traffic that impedes everyone. All of this will decrease robotaxi profits and slow robotaxi take-up, which will have cumulative effects: compared to a world where robotaxis are common and popular, our cities will be less safe, less convenient, and more expensive to live in.

So robotaxi exploitation is a problem. How should we respond?

Four possibilities suggest themselves: acceptance, authority, separation, and culture.

Path 1: Acceptance

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

When a social problem emerges, the easiest thing to do in response is nothing. We can imagine that happening here.

Of course, we won’t frame it that way; no one likes imagining themselves as inert. So cities that go this way will describe what they are doing is reclaiming streets for people. Residents will post videos of children safely crossing mid-block, of elderly residents no longer rushing to beat the light. They'll call it progress.

In this world, we will simply accept that pedestrians exploit the AV tendency toward caution, or even celebrate it. At first it will seem positive. Brief delays here and there, which the robotaxi passengers, absorbed in their phones, will barely notice. The robotaxi operators, aware that they need to maintain their social license to operate, will say nothing.

But the effects will compound. As more pedestrians realize they can cross mid-block without consequence, they do. And the behaviour will spread: cyclists will discover that AVs always yield, and stop checking before merging. Delivery drivers will learn that double-parking in front of a robotaxi doesn’t create a confrontation, just patient waiting, and will yield to the pressure of their schedules and double-park. As robotaxis proliferate, the sum total of these behaviours is to cause the urban traffic system to seize up.

Time-insensitive passengers might not mind. If you're in a Waymo answering emails, what's another five minutes? But time-sensitive travelers—parents racing to daycare pickup, workers trying to make shifts, anyone with a connection to catch—will abandon robotaxis entirely. Transit agencies will watch their ridership decline as buses get mired in the same patient paralysis as robotaxis. Emergency vehicles will find their response times creeping upward, not dramatically, just enough that the marginal heart attack victim doesn't make it. Freight delivery, already struggling with last-mile economics, will find costs rising as each delivery takes just a bit longer.

The city that chooses acceptance isn't actually choosing streets for people. It's choosing a slow-motion breakdown of urban mobility, where the ability to cross anywhere meets the practical need to get somewhere. It's paralysis cosplaying as people-first planning.

Path 2: Authority

Replace Danger with Formal Deterrence

The most obvious way to proceed is to sanction other road users who interfere with robotaxi operation. Robotaxis are already equipped with sensors, making them rolling panopticons; cities might lean into that feature. The robotaxis capture violations; automated systems identify the perpetrators, either by license plate or by facial recognition; and automated citations, with financial penalties, follow. Deterrence is restored, with civil rather than physical penalties.

I’m opening with this one because it is also obvious that this will never happen, at least in the West.

It will never happen because, even assuming that privacy laws and local civil liberties permitted it, no city would ever take the political risk of proceeding this way. It’s already the case that cities are decriminalizing jaywalking, as Virginia did in 2020, Denver and California did in 2023, and New York City did in 2024. The impetus of these reforms was less ‘urbanist’ and more ‘take away discretionary powers police were abusing’, but leave it aside; the trend right now is to give pedestrians more freedom of the road, not less.

AV operators themselves avoid punitive mechanisms, because they know they operate on sufferance and any provocation could get them banned from operating, with dire consequences. This enforcement approach might preserve vehicle throughput by creating predictable deterrence, but it would require developing facial-recognition software to a high degree of quality in ways that doesn’t currently exist, and would also require sustained public commitment to, and investment in, a surveillance state that seems exceedingly unlikely in the West today.

Path 3: Separation

Good fences make good neighbours

If robotaxis are liable to be abused by other modes of travel, one solution is to eliminate interaction among those modes by giving robotaxis dedicated space reserved for their use.

This isn’t a new approach, and reflects what we’ve done with modes for decades, long before AVs came along. Freeways are typically reserved for automobiles, and bike lanes for bikes. Heavy rail commuter trains and subways have segregated rights-of-way in railbeds and tunnels. Sidewalks are reserved for pedestrians. In all these cases, the best way to make a mode run efficiently is for it to be reserved for that mode, so that compromises aren’t required, and costly safety margins don’t need to be built. Conversely, modes that aim to combine uses—multi-use trails for pedestrians and cyclists, or streetcars and buses that operate in mixed traffic—feature conflict: faster modes are slowed down, and slower modes are menaced.

Mode separation is easy when space is unconstrained, but urban places are by definition constrained. How do we offer mode separation here?

It will be hard. It would require the political will to designate lanes in the road for automated vehicles only, and installing infrastructure to ensure it: bollards, curbs, even fences. That is a substantial ask of the public realm, but we've seen it done in some cities for the benefits of bikes or transit, so it's not impossible.

For robotaxis, this might mean downtown cores with AV-only arterials, where the machines can operate at full efficiency, coordinating with each other at intersections without lights, maintaining optimal following distances, moving in platoons. Pedestrians would cross but only at designated points.

In return for this concession, of making some streets much more car-friendly, others would be come much less so. Some cities feature 'naked streets' where there are no curbs, and all travel modes—pedestrians, cyclists, and cars—mingle freely, all moving at the speed of the lowest common denominator. Such spaces are rare today because we can't trust human drivers to move that slowly; but we can trust AVs to do so. They'd travel slowly, of course; they'd have to. But a street network of arterials on the perimeter of neighbourhoods and slow zones within them is perfectly compatible with an effective city-wide transport network. That is what Barcelona is building today, to acclaim, and as I understand it Paris is moving in this direction, albeit slowly.

Slowly is the key factor here. Going this route requires substantial infrastructure investment, which is always expensive and time-consuming. It also requires public consultation and buy-in, which will be difficult to get in a world of NIMBYs, who hate change, and anti-car activism, which hates cars per se and sees any accommodation of them as giving comfort to the enemy.

Starting from scratch, as Sidewalk Labs proposed to do or California Forever is attempting to do now, might be able to make this work. Laying out new roadways that are reserved for robotaxis, and indeed cater to their strengths, say by eliminating traffic lights, is possible in spaces that have never been organized in any other way. But robotaxis are starting to appear in the cities we have now, and must work in those places. Segregation will take too long to be a viable solution to robotaxi abuse.

Path 4: Culture

We’re living in a society, Jerry

We’re not doing well so far. Path 1 is craven surrender; Path 2 just won’t work; Path 3 is infeasible except for greenfield construction or on very long timelines. Are there any good and viable options?

There’s one, which is to recognize abuse of robotaxis is abuse, and to call it out.

This might sound naïve, expecting people to behave well simply because they are asked to do so. But it has happened before. I am old enough to remember when smoking in restaurants was common, but today, lighting a cigarette indoors would not only earn you a citation, but social horror. Laws did change, but the primary cause was an emerging, widespread, collective agreement that smoking in shared spaces was inconsiderate.

Other examples abound. Failing to recycle, or to clean up after your dog, or to cut in line; these incur mild or even no civil penalty, but a substantial social cost. The same evolution could happen with robotaxi exploitation. The key is reframing the act. Cutting off a robotaxi isn’t about sticking it to Big Tech, it’s delaying the nurse heading to their shift or the elderly person who can no longer drive themselves. Abusers aren’t reclaiming the streets but making them worse for everyone.

Robotaxis themselves can incorporate features to deter abuse. Some enthusiasts fantasize about physical deterrence, from as mild as a water gun to as severe as a cattle prod, but this sort of physical interference would not only be illegal, but also would be counterproductive, as inevitably an innocent person would suffer from it, bringing the whole sector into disrepute. Cultural deterrence is far better: a loud alarm that goes off when someone interferes with a robotaxi, drawing the attention of everyone on the street, so the offender is suddenly the object of attention. Perhaps an even more effective approach would be public shaming by a teleoperator, whose PLEASE STEP AWAY FROM THE VEHICLE is broadcast by loudspeaker.

The beauty of this approach is its fluidity. Laws are rigid; infrastructure is fixed; but norms evolve with circumstances. As AV technology improves, as traffic patterns shift, as cities change, cultural expectations can adjust accordingly. I think we can already see early signs of these norms developing. In San Francisco, where Waymos are common, there's already social policing happening.

This video offers an example of it. We don’t need to give Inside Edition too much credit: this is about fear-mongering, farming stories of vulnerability for attention. But whatever their motives, spreading stories like this one helps to establish the cultural norms that interfering with robotaxis like this is a low-status move that only the contemptible engage in. We need more of it.

Choose Your Fighter

Danger used to enforce our street etiquette without deliberation or design. We didn't need to articulate why pedestrians shouldn't step into traffic; risk of harm made the argument silently but effectively. AVs remove that enforcer, forcing cities to be explicit about their values and make conscious choices about order.

Will you choose authority—the formal deterrence of cameras and citations? This preserves traffic flow, but at the cost of privacy. In my view, it has quite a bit to be said for it, but I wish you luck persuading a majority of the citizenry to accept this approach.

Will you choose acceptance—taking slower vehicle movement as the price of human-centred streets? This path creates more liveable cities and acknowledges that streets serve social functions beyond transportation, but it adds friction to the streets that will posts costs to business, goods delivery, emergency response, and the ability to travel quickly to anywhere that rapid transit doesn’t reach.

Will you choose separation—engineering the conflict away through infrastructure? This buys predictability and efficiency through physical design, but it will be expensive and take years, or even decades.

Each choice encodes different assumptions about the purpose of streets and how we expect urbanites to behave. That’s why I think you should choose none of these, and instead choose culture. Unlike authority, it aligns with our intuitions about how public space should operate. Unlike acceptance, it admits that there is a problem here. Unlike separation, it is (relatively) cheap and fast to build, and scales well.

The temptation will be to muddle through: add a camera here, hive off a lane there, and otherwise continue as we have. That guarantees the worst equilibrium: AVs that stop for everyone everywhere, people who exploit it systematically, and cities that inherit delays without dividends. We’ve begun well, by programming our machines to behave safely. The next step, to ensure we avoid that bad equilibrium, is to program ourselves.

I've always envisioned the ped-car conflict as being one of the riskiest part of the whole AV concept. I can imagine a bunch of university students on a Friday night just "taking over" major arterials simply by walking in groups across or on the road, knowing that all vehicles are programmed to avoid them. Of course, this won't really be an issue until the time when all vehicles are programmed in this manner, but pedestrian avoidance systems will soon come to all new vehicles and not be limited to AVs.

Some would say that by removing the danger of car-ped conflict, we are making life better and more ped-friendly, but you are right in noting that it is the risk / danger of such conflict that provides effective "silent policing" today. Absent such "silent policing" I think we would have to move to more "active policing", combined with physical barriers, ped bridges, and fences to control mid-block ped crossings. So we'll end up with a more rigorous separation, higher cost, and a worse pedestrian environment (and greater auto dominance of the street). Not much of a bargain. I don't see a viable universal solution to the problem, but you're right in that the answer has to lie in cultural behaviour rather than "engineered" responses. But how to control / create / manage cultural behaviour in this manner?