This Is Your Brain on Cars

The hidden psychology of vehicle ownership

One day soon, robotaxis will be everywhere: in every city and most suburbs. If all goes as we hope, they’ll be clean, they’ll never crash, and they’ll arrive within three minutes of you hailing one. And they’ll be cheap, at perhaps 40% to 60% of the cost of ridehail today. The simplest financial analysis will show that giving up car ownership is the right move.

And yet private cars will still be everywhere.

There are lots of reasons why. Some people will have lifestyles that make private ownership the right choice, like parents of young children or workers with lots of equipment. Others will have well-founded fears of things like wildfires, invasion of privacy, or simply the inability to reach all the places they need to go without their own car.

These are barriers that we have discussed before. What they have in common is that they are reasonable and well-founded concerns.

Today, let’s draw on the work my co-authors and I present in The End of Driving (forthcoming in August!), to talk about the other barriers: the ones that aren’t reasonable, aren’t well-founded, and as such are amenable to thoughtful change.

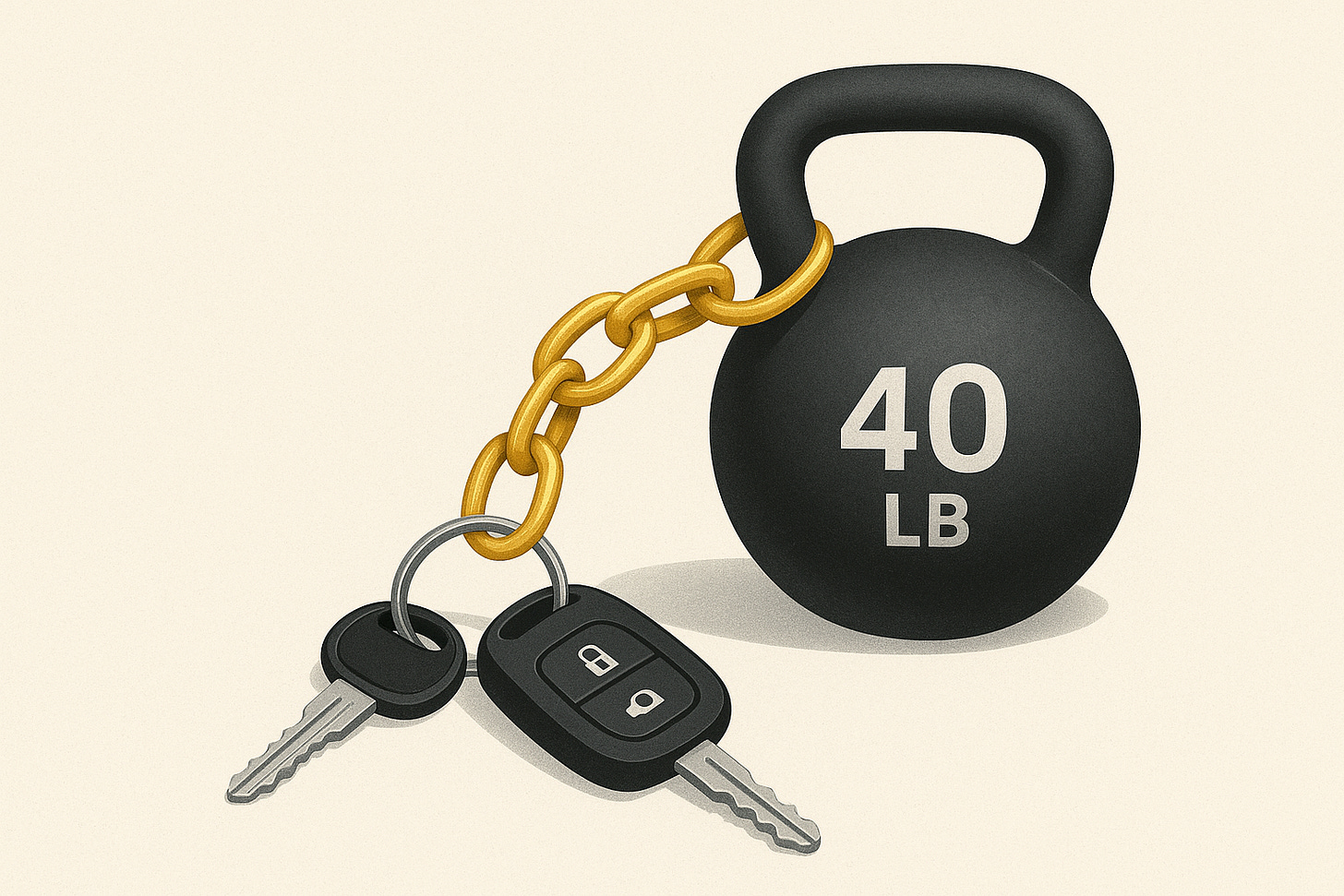

The Invisible Car Tax

The average Canadian household spends more than $9,000 annually on vehicle ownership. That’s a rolled-up figure that includes actual expenditures like insurance, maintenance, fuel, and parking, as well as the notional cost of depreciation. For many families, their car is their second-largest expense (housing is first, food third). For American households, the costs are even greater: Americans drive more, pay more for insurance, and typically own larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles.

Every household is different, of course. Some will not be able to give up their cars in favour of robotaxis. But many will be: at a first approximation, every household whose annual robotaxi bill would be less than $9,000 (in today’s dollars) should strongly consider it. At least, if that household is made of cold-blooded rational calculators.

But of course they are not, because almost no one is a cold-blooded rational calculator. Recognition of this fact is the foundation of behavioural economics, the study of how psychological, emotional, and social factors systematically influence economic decisions. Understanding these psychological forces is crucial because they create powerful barriers to rational transportation choices. Four of those forces are key to how we think about cars and alternatives: mental accounting, the endowment effect, loss aversion, and optimism bias.

Mental Accounting

Mental accounting is shorthand for the fact that we evaluate similar costs differently depending on how they're framed and when they occur. I mentioned earlier that the average Canadian household spends more than $9,000 annually, on net, on vehicle ownership. Yet as per the CAA, three in five car owners underestimate their annual driving costs by more than $4,000.1 A $300 monthly car payment is predictable and planned and budgeted for, but gasoline prices fluctuate, parking costs vary, and maintenance expenses feel occasional rather than systematic, and aren’t easily connected in memory to a particular trip. This makes those costs hard to notice, or remember, or estimate. Meanwhile, each $45 robotaxi ride across town will feel expensive, because it's a single, visible transaction, meaning that—even though it’s a better deal—it will feel worse than paying $9,000 over the course of a year in scattered, unpredictable, variable sums.

The Endowment Effect

The endowment effect is the fact that owning a thing makes us value it more highly than we would if we didn't own. Demonstrating this effect helped get Daniel Kahneman a Nobel Prize. In his classic study, he divided a group of people at random into two groups. In one group, each person was given a coffee mug, theirs to keep. In the other, each person was given money (roughly the retail price of a mug), also theirs to keep. Both groups were told the mugs could be sold, if a buyer and seller agreed.

If everyone involved was rational, you’d expect about half of the mugs to change hands, as the groups were randomized, so desire for mugs versus cash should have been roughly equal in each group. But in fact only about 10% to 20% of the mugs were sold… because mug-havers typically would only sell for twice what mug-buyers were willing to pay. Even though they had just been given a mug, and presumably didn’t need it, the fact that the mug-havers owned the mug generated attachment.

Cars trigger this effect more powerfully than almost any other possession, because your car isn’t just a method of transport, it’s also a private space. Its seat is set to make you and only you comfortable, and it’s full of your own things. More than this, a car today is not just physical; it's software-defined. Your Bluetooth, your GPS memory, your Spotify history, even your climate preferences, are all connected and remembered, even to the extent that they make the car less useful as a vehicle.

Few other goods could feel so much like a part of you.

Loss Aversion

A close relative of the endowment effect is loss aversion: the tendency for losses to feel worse than equivalent gains feel good. This psychological asymmetry was first quantified by Kahneman and Tversky, who found that people typically need gains to be roughly twice as large as losses to feel equivalent satisfaction. The principle explains why someone might drive across town to save $50 on a $200 purchase, but wouldn’t make the same trip to save $50 on a $2,000 purchase. The loss in the latter case is 2.5% of the total cost, but in the former, it’s 25%. Such a large percentage feels hard to bear, while the smaller one feels tolerable, just part of doing business… even though the absolute figure of $50 remains the same, meaning that one’s willingness to save it should be identical in each case.

When applied to car ownership, loss aversion creates a particularly stubborn barrier to change. As we have discussed before, giving up your car will feel like losing freedom, control, privacy, and status all at once—losses that your brain processes as immediate and visceral threats to your current state. The benefits of robotaxis, however compelling they might be on paper—lower costs, reduced parking hassles, no maintenance headaches—register as mere potential gains, abstract improvements to a future state you don't yet inhabit. These gains will never feel as intense as those losses, because your brain treats the certain sacrifice of what you have as more significant than the possible acquisition of what you might get.

Optimism Bias

Optimism bias is our tendency to overestimate our own abilities and underestimate risks to ourselves. Research consistently shows that 80%–90% of drivers believe they're better than average… which, of course, is statistically impossible. When you tell a confident driver that robotaxis will reduce accidents by 90%, they don't think about the thousands of lives saved annually; they think instead about how they don’t cause accidents with their superior driving, which means driving automation will take away their ability to drive, not grant them freedom from worrying about the risk of a road incident.

Worse, doing one’s own driving intuitively feels safer, even though it isn’t, because the driver is doing something. Riding in a robotaxi will always feel passive, and people hate feeling passive in risky contexts. (It’s a major component of the fear of flying.) Automation’s chief benefit, that driving passes out of one’s own control, is the thing that will make many people unable to accept it.

It would be bad enough if private cars were simply likely triggers for these foundational biases. But matters are even worse than that, because car ownership also serves a particular psychological function: the expression of our identities.

The Honda Civic? Practical. The Ford F-150? Rugged and dependable. The Prius? Green and sustainable. The BMW? Lavish and select. And on and on. Owning a car is a way to tell the world—and, critically, yourself—what kind of person you are. There is some reason to believe that this effect is waning due to generational replacement, and that younger people are less susceptible to it; but recent events have made it very clear this phenomenon is still with us. How else to explain the anti-Elon bumper stickers for your Tesla, which I have mocked before: Musk’s antics have changed the message that a Tesla sends, and for people who valued the Tesla for its ability to tell the world who its owner is, that change is excruciating.

Robotaxis can’t do this work for us. If transportation is merely a service rather than a possession, it can’t reliably signal anything about you. Robotaxi rides will offer efficiency, but not identity.

The Availability Heuristic

Nor is that all. Another psychological quirk will hinder robotaxis: the availability heuristic, i.e., our tendency to judge the probability of events by how easily we can recall examples of those events. Every robotaxi accident will make headlines, because those are easy to identify and remember; the thousands of times that a robotaxi drives safely and averts an incident will remain unnoticed. Even innocuous events will easily pattern-match to more sinister ones, despite the fact that there is no connection between them.

We saw this dynamic play out today; despite data showing that Waymo robotaxis have significantly lower accident rates than human drivers, media coverage, seeking clicks, highlights even incidents where nothing happened as matters of concern. This sort of narrative, focused on the dramatic and unusual rather than the statistical reality, reinforces our behavioural biases in unhelpful ways.

Designing for Human Nature

I want to stress that none of these psychological tendencies are character flaws. They are, instead, innate, sturdy, and predictable features of human psychology. They are gifts from evolution that helped us, in the ancestral environment, to make quick decisions with incomplete information. No one should feel guilty about these tendencies, but everyone should try to overcome them; not least because they create systematic barriers to adopting superior transportation options.

It’s not all bad. If we understand these psychological tics, advocates for a robotaxi future—variously policymakers, progress advocates, pop-culture tastemakers—can exploit them, each in our own fashion, in service of the cause of robotaxi abundance.

There seem to be several ways we can do so:

We can reframe ownership as burdensome. We won’t ask people to give up their cars. Instead, we’ll ask them to put down the burden of owning a car. We can point out the obvious, that car ownership requires a big upfront cost for a depreciating asset, and one that requires regular payments for insurance, maintenance, fuel, and parking. Car ads present ownership as freedom and liberty to go where one wishes, without constraint. The counterpoint is that ownership is a constraint; it is ridehail, in a cheap and omnipresent robotaxi, that actually will liberate.

Similarly, we can reframe ownership as loss, to make loss aversion a force that pulls toward robotaxis rather than private cars. These losses already exist, but are not obvious: money that could be spent on other things, time spent in traffic that could be productive, and stress from driving in dangerous conditions. Recognizing these losses will level the playing field, removing the tilt in favour of ownership.

We can create new identity signals. Early robotaxi adopters should be just as free to signal their values and selves as car owners. It’s easy to see that sort of self this advertises: a mark of sophistication, commitment to sustainability, and financial savvy. The hard part is to do so visibly, without the concrete and visible vehicle to do it. Call the people who did Apple’s lifestyle marketing and get them on the case (I still remember the dancing silhouettes that hyped iPods, even twenty years after the fact). Apple made its customers feel innovative and creative; robotaxi firms should do the same, making users feel like forward-thinking urbanites, not like people who can't afford cars.

Finally, we can nudge people toward the robotaxi outcome by making robotaxi use as frictionless as possible, while adding friction to car use. The former is something that robotaxi firms will doubtless work with cities to achieve in any case: dedicated pick-up-and-drop-off zones, seamless payment systems, and even areas restricted to self-driving cars will shift the convenience equation. Meanwhile, dynamic parking pricing and reduced parking availability can highlight ownership costs. For an example, look to Singapore, which boasts world-class public transit, seamless ride-hailing integration through designated pickup zones, and the requirement to obtain a Certificate of Entitlement, which can cost more than $76,000 USD, before being permitted to own a car. The result is one of the world's lowest car ownership rates (only 12 cars per 100 people) in a prosperous metropolis, achieved through smart policy.

It’s been a trope of planning, and policy-making, for centuries that people make rational choices based on cost, time, and convenience. And for the most part, they do; the theory of ‘false consciousness’, that people consistently misunderstand their own interest, is far too strong. But it is certainly the case that in some edge cases, confusion can creep in. In a competitive marketplace of goods and ideas, we should expect that expert sellers will identify and exploit those edge cases. Progress advocates shouldn’t cede that ground to marketing executives.

At scale, robotaxis will have superior economics and functionality to private ownership, but that’s not enough. Success—defined here as replacing the mostly human-driven, privately-owned, single-occupancy vehicles that fill city streets with robotaxi fleets—will require not just solving the technical challenges of driving automation, but creating new emotional narratives around transportation that resonate with our needs for identity, control, and social belonging.

Private cars have a century-long head start in building emotional connections with their owners. They're woven into our senses of identity, freedom, and social status. Any prediction about the future must take that weaving seriously. But these advantages aren’t insurmountable. We know how the spell was cast.

Which means that, if we choose, we can break it as well.

Respect to Emma McAleavy, Julius Simonelli, and Jeff Fong for comments on earlier drafts.

That figure is getting stale, as it comes from a 2013 report, but more recent work by CAA suggests that the underestimation continues.