The Mysterious and Perpetual Shortage of Truck Drivers

…and how driving automation can solve it

North America has been suffering from a shortage of truck drivers… for decades, apparently.

Here is Werner Enterprises complaining in 1998 that “there have been shortages of drivers in the trucking industry”, that they anticipate that “the competition for qualified drivers will continue to be high”. Here is TruckingInfo.com’s retrospective of its coverage of the industry in the 2000s, and its series ‘Coping with Crisis’, the first element of which was a driver shortage. Here is CCJ Digital’s breathless special report from 2018, titled ‘Day of reckoning in driver shortage saga’. And here’s Axios in 2021, reporting on the acute shortage during the pandemic.

In 2025, the crisis continues. The American Trucking Association claims the U.S. needs 80,000 more drivers, while Transport Canada says we’re short 25,000 and counting.

But it’s a strange crisis. If we look to the numbers—employment figures, wage trajectories, vacancy rates—we don’t see an industry hemorrhaging workers. Canadian truck drivers saw their average hourly wage climb from $24.05 in 2021 to $27.10 by the third quarter of 2024, a trajectory that outpaced inflation for much of that period, according to Statistics Canada’s Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. In the United States, median wages for heavy and tractor-trailer drivers reached $57,440 in May 2024, continuing an upward trend that began accelerating during the pandemic.

Meanwhile, vacancy rates are falling, not rising. The recent peak for Canadian truck driver vacancies was 28,250, in 2022. But by the third quarter of 2024, that number had fallen to approximately 15,350, with U.S. data reveals similar patterns. Most tellingly, the actual supply of drivers has grown substantially over time: there are more than 1.5X drivers today than there were in the mid-1980s in both countries.

What is going on here? How can an industry employ more people than ever, at the highest wages in decades, and yet still be offering a narrative of perpetual crisis?

The Long Shadow of the 1970s

To answer that, we need to turn our attention back even further than the 1990s. Anyone much younger than me won’t believe it, but there was a time—a moment, really, from about 1975 to 1985—when long-haul trucking had immense cultural clout.

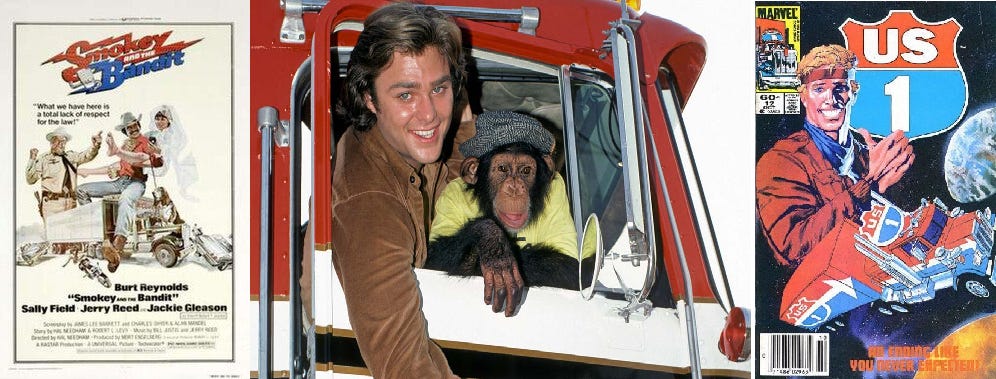

There were truckers on film, most notably in Smokey and the Bandit (1977), where Burt Reynolds outran state troopers to smuggle Coors beer across state lines, though I was more partial to Clint Eastwood in Every Which Way But Loose (1978), who drove a big rig while pursuing a side hustle as a bare-knuckle brawler. Clint also found time to take care of a pet orangutan, which inspired a prime-time TV knock-off, B.J. and the Bear (1979–81), a series about a trucker and his pet, a chimpanzee. There were truckers on the radio, like in C.W. McCall’s Convoy (1975), and in Marvel Comics, which launched U.S. 1 in 1983, featuring a trucker superhero traveling the country, delivering orders and battling injustice.1

This celebration of the trucker in popular culture reflected genuine social standing. Thanks to strong Teamsters contracts, long-haul drivers had excellent wages relative to other blue-collar jobs: driving a rig could support a family, buy a house, and put kids through school. Combine the job’s earning power with the long-standing romance of the road—its associations with noble solitude and independence—and trucking, for all of its difficulty and long hours, seemed, for many, like an aspirational, even ideal, role.

The reason trucking paid so well was that the industry was highly regulated, with the Interstate Commerce Commission making it difficult for new firms to enter the market, and dictating to established firms what routes they could use. The lack of competition allowed incumbent firms to charge high rates, which made both management and labour happy… at the expense of consumers, which had to pay more for limited options.

In 1980, the President signed the Motor Carrier Act, deregulating interstate trucking and opening the industry’s doors to low-cost competitors.2 Dozens of small firms emerged, many of which were not unionized. Profits dropped, and per-mile pay rates shrank. The world shown in B.J. and the Bear was disappearing even as the show aired. Trucker wages fell by more than 25% in real terms between 1978 and 1990, along with predictable routes, ample home time, and density of union membership.

This is the root of the ‘driver shortage’ narrative. Trucking’s cultural image peaked just as its economic foundation was crumbling. That historical collapse still haunts the industry’s collective memory. Even though wages have been rising in recent decades, they remain below their late-1970s peak in real terms. The U.S. trucking workforce remembers—or inherits memories of—when driving truck meant middle-class stability without caveats or asterisks. Canadian drivers, while experiencing slower but steadier wage growth over the decades, absorb these narratives through cross-border industry culture.

Turnover, Not Shortage

This wage pattern is important, because it tells us what kind of problem we’re dealing with here.

Think about industries facing genuine worker scarcity. Today, that’s AI researchers, who are in such short supply that Meta is offering nine-figure contracts to join their team. Fifteen years ago, it was coders, or—closer to the trucking model—workers in the Alberta oil patch. In all these cases, we see competition among employers, reflected in offers of high compensation.

Notably, this is not what we see in trucking, which suggests scarcity is not really the issue.

The actual issue is that there isn’t one trucking industry, but two. On the one hand, there are private, in-house fleets for large firms. Walmart’s proprietary drivers earn packages approaching $110,000 annually, enjoy predictable schedules, and sleep in their own beds most nights. These positions have waiting lists, because their turnover rates hover below 15%. Similarly, unionized positions at companies like UPS and FedEx maintain similar stability. In this part of the trucking sector, the job can retain workers and attract new ones.

On the other hand, there are mega-carriers—names omitted to protect the guilty—that offer long-haul positions that pay by the mile. Here, annual turnover rates exceed 90%. Put another way, that means nine out of ten drivers leave before spending even one year in the role.

Why is the profession so toxic to newcomers?

Start with the fact that the profession is defined by unpaid labour. Drivers are typically paid for the miles they drive… and only those miles. But their role requires them to do much more than drive. Mandatory pre-trip inspections take 30-to-45 minutes daily. Paperwork at shippers and receivers takes time. So too does fuelling; maintenance; and, in some cases, helping to unload the truck so you can get back on the road. When you’re paid by the mile but spend 40% of your time on non-driving tasks, your effective hourly wage plummets.

But compensation is only part of the issue; there’s also the physical and psychological toll. Eleven hours of sitting still and maintaining lane position curves the spine and slows the circulation. Truck stop food eases the pain, but spikes blood pressure and waistlines. Sleep and exercise are intermittent. The social isolation is, in its own way, just as corrosive; hours spent on the road are hours spent away from spouses, children, and friends.

Thanks to these terrible working conditions, the roughly 500,000 positions at major U.S. carriers experience 90% annual turnover. This means that companies must recruit, train, and onboard ~450,000 drivers annually just to maintain current capacity. Each recruitment costs between $8,000 and $12,000. That’s $4 billion spent annually on a problem that better-run segments of the same industry have already solved.

This is why the narrative of driver shortages persists: because the industry conflates high turnover with insufficient supply. Carriers must recruit 450,000 drivers annually just to maintain current capacity, which certainly looks like shortage. But what we're actually seeing is a retention crisis so severe that it mimics the symptoms of scarcity.

Which raises an obvious question: why don’t market forces fix this? If turnover costs billions and better conditions reduce turnover, why hasn’t some enterprising carrier cracked the code?

The answer is market failure in the form of a collective-action problem. Large carriers are locked into contracts with shippers like Amazon who’ve optimized their entire supply chains around cheap freight. These shippers, to minimize cost, let out their shipping contracts in reverse auctions where the lowest bid wins. This means that carriers have to optimize for low bids if they want to win any work. So carriers are free to invest in driver retention, but that won’t help them in the auction: they’ll face higher costs, but can’t charge more if they want to win work. If all carriers simultaneously improved conditions, freight rates would rise to accommodate the costs, and everyone would benefit from lower turnover. But everyone must cooperate to make it work. No carrier can move alone without being destroyed.

Regulatory capture ensures this system persists. Trucking companies successfully lobbied for exemption from federal overtime requirements in 1938 and have defended it ever since. They’ve fought against detention time pay mandates, hours-of-service reforms, and minimum wage protections. When California required employee classification for drivers, the industry got federal legislation to override it. Through its trade associations and lobby groups, the industry acts to ensure that the rules favour carriers over drivers.

The result is a market that’s locked into dysfunction. Each actor behaves rationally within their constraints, but the aggregate outcome is irrational. Drivers flee because conditions are intolerable. Companies can’t improve conditions because competition won’t allow it. Shippers won’t pay more because they don’t have to. And regulators only tinker around the edges. The wheel keeps turning; the shortage persists.

Automation Can Break the Cycle

Readers of Changing Lanes know that this newsletter believes in the power of technology, and specifically vehicle automation, to break us out of bad equilibria. Public transit is stuck in an endless emergency of its own, but here we believe that automating transit vehicles would allow transit agencies to operate better service more cheaply, making everyone better off.

What is true of public transit is equally true of trucking.

I am bullish about the power of automated vehicles to revitalize this sector, to the point where I am co-chairing the Canadian Automated Vehicle Initiative’s project to have a driverless truck travel from Halifax to Vancouver in 2028. If we succeed, we will execute the longest fully-automated heavy truck journey ever attempted, stretching 6,000 kilometres across eight provinces… and in so doing, prove that automation can safely handle long-haul Canadian conditions, and set a new global benchmark for what the technology can achieve.

To be clear: what I think it can achieve is to solve the specific operational problems that make the trucking sector so difficult for drivers, firms, and customers.

An automated truck can maintain lane position for hours, even days, at a time, enduring what for a human would be grinding, health-destroying monotony, without suffering; and can do so while operating more safely than any human could. It’s early days in automated trucking, but to date automated trucks have driven 10 million miles globally without a fatality. They can operate through the night when highways are emptier, improving asset utilization and allowing for faster goods movement, without grinding down the driver or putting other road users at risk. And they won’t suffer wage theft when they’re sitting idle.

The path to widespread adoption won't happen overnight, but it's closer than skeptics may imagine. Aurora Innovation plans commercial deployment on the Dallas-Houston corridor by late 2025. Kodiak Robotics is targeting 2025–2026 for driverless operations. These are commercial ventures with customers, routes, and revenue targets. This is why we propose to launch our CAVI project for a cross-Canada journey in 2028: late enough to benefit from early deployments' lessons, early enough to influence the technology's evolution.

The adoption curve will follow a pattern we can forecast. First, the simplest routes: interstate highways (and, if I have my way, their Canadian equivalents) in good weather between major hubs. Then expansion to more complex routes, adverse weather, and smaller destinations. This will take time, which means that today’s long-haul truckers won't be thrown out of work; as the industry matures, they'll have the chance to move into better-compensated, more humane roles that automation can't touch.

I want to emphasize that point: the advent of automated trucking will be good for drivers.

It will be good because it will break the collective-action problem that has trapped the industry since deregulation. When carriers deploy automated trucks, they will escape the problem of driver turnover, and that means they will be able to escape the race-to-the-bottom entirely, competing on service quality as well as on price. That’s good for the carriers, and good for human drivers too, who will still be handling the complex, high-touch deliveries that automation won't handle for decades. When automated trucks take over the grinding highway miles, human drivers can focus on the first-mile, last-mile, and specialized hauling that pays well and lets them sleep at home.

Thanks to these benefits, automation has the potential to disrupt the bad equilibrium we’ve been living with since the 1980s. It can do so not by ‘solving a shortage’, because there never was a shortage to solve, but rather by addressing the operational dysfunctions that created the appearance of shortage. Automation, if we deploy it wisely, will solve the problem we haven’t known we’ve had. It can mean that, if we get it right, the 2030s could see a return to the 1970s, with trucking regaining its middle-class promise, through technology that makes the worst parts of the job obsolete.

This excerpt from U.S. 1’s Wikipedia entry, on the series’ antagonists, is too delightful to pass over. The series’ villains included “Mary McGrill, waitress at the Short Stop Diner, [who] had an alternate personality, the villainess Midnight, who used a mind-controlling bullwhip… Jefferson Archer (Highwayman), U.S.'s brother who turned to evil… [and] Baron Von Blimp, a villain based out of a dirigible”.

As the year suggests, that’s not President Reagan, but President Carter, who in recent years was lauded by such unlikely parties as the American Economic Institute and the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page as a ‘champion of deregulation’.

Is this really a "market failure", or just an honestly shitty situation from the point of view of truck drivers (who can't hold out for better working conditions because there are too many other workers who are willing to put up with the status quo)?

> If all carriers simultaneously improved conditions, freight rates would rise to accommodate the costs, and everyone would benefit from lower turnover. But everyone must cooperate to make it work. No carrier can move alone without being destroyed.

If carriers are acting rationally, it must follow that they find the high turnover worthwhile because raising wages sufficiently to reduce turnover would cost more than dealing with driver churn? If carriers were able to band together to force higher freight rates, couldn't they just pocket the higher rates and continue enjoying today's low wages?

Or if carriers are in fact acting irrationally (I know nothing about the trucking industry so I don't know whether this is plausible), that would imply that even under current freight rates, a carrier could improve their situation by paying higher wages, and making it up in reduced recruiting costs and other overhead?

If *workers* could exercise collective action, then they could negotiate better wages / working conditions. And yes, if automation shifts the optimal mix of human labor toward less-shitty work, that could also benefit workers. It would be interesting to see further exploration of how the job of a trucker might evolve as self-driving trucks enter the market.

Be careful - using an image of a driverless truck straddling the lane line, unnecessarily in the left (passing) lane, on an empty mountain highway isn't really helpful....

And in the automated truck future, would there be no cab, just a (simpler, cheaper, smaller) motorized tug? And then switch to a cab-with-driver if needed for last-mile operations?