Better Than Whom?

We need to decide how to measure AV safety

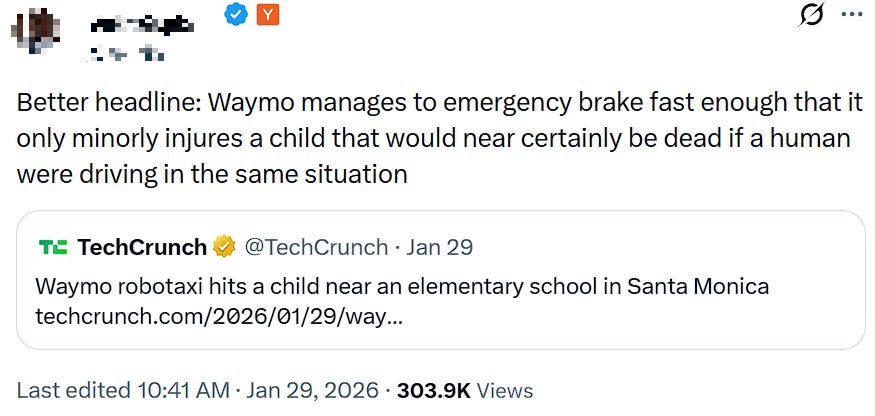

A few weeks ago, on 23 January 2026, a Waymo robotaxi struck a child near a Santa Monica elementary school.

It was the morning, and many parents were dropping off their children, meaning that the situation was as rich with incident as one might expect: children on the sidewalks, a crossing guard, and lots of double-parked vehicles. As the Waymo proceeded through the area, a child ran into the street from behind a parked SUV toward the school. The Waymo slowed its speed and while it did hit the child, they sustained only minor injuries and were able to walk away.

In the wake of this incident, I saw lots of people on X come to the company’s defense, making the argument that had a human driver been operating the vehicle, the accident still would have happened, but lacking the Waymo’s digital vision and ‘reflexes’, the collision would have taken place at a higher speed. In that case, the child would be gravely injured or likely dead, as opposed to being able to walk away from the incident.

Waymo made a similar claim, arguing that in fact this incident demonstrated “the material safety benefit of the Waymo Driver”.

Let’s stipulate two things immediately: the claim is almost certainly true; and it’s almost certainly a bad communications strategy. Given that Waymo’s most-important selling point to the public is that driving automation will reduce the frequency of road incidents, arguing that the Waymo Driver hurts people less is actually an argument for the firm’s opponents.

But leave it aside. As an advocate for driving automation generally rather than any particular firm, I have no stake in Waymo’s fortunes. But I do have an interest in this technology spreading widely, which is why, to me, the interesting question here is why Waymo and the firm’s supporters expected this argument to carry the day.

The answer is a disagreement about benchmarks. The driving-automation sector, its critics, and its regulators are measuring automated-vehicle (AV) performance against different standards.

I think there is a right benchmark, but it’s harder to defend than its proponents admit, and harder to dismiss than its opponents would like.

Choosing a Benchmark

Intuitively, when we think about an AV company’s safety record, we compare their automated-driving systems (ADS) to the general driving population. The denominator includes every driver on the road: not only the attentive and calm, but also the sober and drunk, attentive and texting, the seventeen-year-old with a learner’s permit and the eighty-year-old who should have stopped driving years ago. Against that population as a whole, a well-engineered ADS looks very good. It doesn’t drink, nor text, nor doze off, nor even fiddle with the car’s audio system. That means that an ADS is indeed better than the average, which is a valuable improvement we should want to see implemented everywhere. Impaired and distracted driving kills tens of thousands of people a year in North America, and eliminating those deaths would be a historic achievement.

But is this the right standard?

An ADS that outperforms the average is outperforming a benchmark that includes the worst. And indeed Waymo takes this into account by also employing what it calls the NIEON standard: Non-Impaired, Eyes ON. This standard refers to a hypothetical human driver who is always attentive and never tired. If the Waymo Driver (its ADS) can outperform this standard, the safety value of the service is established even more strongly.

Even stronger standards are possible. Phil Koopman, a researcher who has worked on self-driving car safety for decades, argues that the right comparison is to a “careful and competent” human driver who adjusts behaviour based on context. Under this benchmark, the relevant question about the Santa Monica crash isn’t reaction time. It’s whether the vehicle was driving with a level of caution appropriate for a chaotic school drop-off involving double-parked vehicles, a crossing guard, and visible children. A careful human driver approaching that scene slows down before any child runs into the road; they slow down because they expect that just such a thing might happen. If the Waymo didn’t, the crash isn’t “unavoidable.” It’s a predictable consequence of insufficient contextual awareness.

Koopman is pointing to something very important: we can judge an ADS’ performance against several kinds of human driver, and our choice of comparison class, applied to the same incident, produces different conclusions. On one view, the Waymo vehicle performed well: it detected the child and braked faster than a typical human would have managed given the same perception-response constraints. Call this the ‘Average’ standard. On another view, the same crash is a failure: a prudent driver would have been going slower before the child appeared. Call this the ‘Professional’ standard.

The latter is what we already apply to people who drive for a living: bus operators, truckers, or taxi drivers. AVs are, or aim to be, commercial vehicles carrying paying passengers on public roads. In such cases, we have appropriately higher expectations. A bus driver who hits a student near a school is judged much more severely than the average motorist, precisely because we expect them to know and perform better. We don’t expect perfection, but competence exercised with care: evidence that the operator understood the environment, acted appropriately within it, exercising reasonable judgment about potential risks and trade-offs. Indeed, this capability is precisely what the term ‘professional’ means.

This argument, that we should hold ADS to the Professional standard, is one I have a good deal of sympathy for.

But it’s also riddled with problems.

Against the Professional-Driver Standard

The first problem is that the Professional standard relies on the concept of reasonableness without explaining how that standard would work for a machine. The critique of the Average standard is that it’s not enough for an ADS to simply follow the rules-as-written without paying attention to larger context and behaving ‘reasonably’ given that context. That critique leaves a basic question unanswered: how is that kind of reasonableness supposed to be defined and applied before something goes wrong?

Professional drivers are not governed by a single, clear rule for how cautious they must be in different situations. In practice, two different professional drivers might behave quite differently around schools, parked cars, or places where pedestrians might be hidden, and we don’t regard that difference as evidence that one or the other is in the wrong. In such cases, we only look for wrongdoing after the fact, by reconstructing the scene, appealing to shared norms, and judging which risks a driver should have anticipated. This is the approach we use in tort law for humans.

For machines, though, reasonableness must be turned into guidance that shapes behavior in advance. If we skip that step, the standard is supplied only after an incident, through judgments about what the ADS should have done… meaning that accountability shifts from clear expectations to after-the-fact storytelling. We would regard that approach as unfair if applied to human conduct, and it’s equally unfair if applied to a machine.

It’s unfair because there is an obvious failure mode here. If reasonable-behaviour-in-context is defined retrospectively, if every crash becomes evidence that the system should have been more careful because ‘look what happened’, then no ADS can ever be vindicated in the case of an incident. Every incident will always be the ADS’ fault, because it will always be possible to say that the incident wouldn’t have happened had the ADS been better.

This problem has some merit. For a machine, reasonableness does need to be translated into guidance that shapes behavior before something goes wrong, and proponents of the Professional standard weaken their case by treating that translation as easy or obvious. There is real definitional work to be done, and it is not obvious that has been.

Applied to the Santa Monica crash specifically, however, any concern with after-the-fact storytelling is hard to entertain. This was a school zone during drop-off hours, with double-parked vehicles, a crossing guard, and children visible on both sides of the street. These are not contextual cues that become legible only in retrospect. They are cues that every experienced driver recognizes. Saying the ADS should have been more cautious here is not merely hindsight bias.

It’s also something we have no difficulty saying about the exercise of judgment in other safety-critical fields, like aviation or medicine. Pilots and doctors both are granted discretion, but are also held to a standard developed through professional consensus (and in some instances, case law). These fields have not collapsed incident review into arbitrary hindsight. That in turn means that automated driving can benefit from an equivalent framework, once we develop one.

The second problem is the downstream effects of the Professional standard. Suppose regulators require an ADS operator to explain, after every serious incident, why the system chose to drive at a given speed in a given context. Those explanations will rapidly harden into informal expectations, which will become de facto rules.

And those rules will become liability triggers.

Anyone who has watched how environmental impact assessments or accessibility standards evolve in practice knows this pattern, and knows where it leads. The final stage of the process will be ADS that avoids complex environments entirely because, though they are safe to enter in aggregate, any individual incident within them will be narratively indefensible. (Not to mention that opportunistic humans will note that abundance of caution and exploit it.) The result is a fleet of robotaxis that only operates on wide, empty boulevards after midnight, which is both legally safe and utterly useless. That’s an extreme I don’t think we would reach—the slope isn’t that slippery—but I’d prefer not to slide any distance in that direction.

This problem is harder to dismiss. We know from our experience of the housing, energy, and environmental-protection sectors over the past five decades that regulatory regimes do calcify, incident explanations do become expectations, and those expectations do become liability triggers. To avoid this risk, we need regulators to state plainly that not every incident in a complex environment implies fault.

The third problem is the unfair asymmetry here. We don’t require human professional drivers to produce a machine-legible account of their risk posture after every incident, because they can’t provide one. Instead, we judge them by plausibility and norms, not by internal-state inspection. Requiring AVs to demonstrate, algorithmically, that they recognized and responded to every relevant contextual cue is a distinct and more demanding obligation, imposed on systems that can be inspected precisely because they can be. The ability to look inside the machine creates the expectation that we must, which creates a standard no human driver, even a professional one, has ever been held to.

This problem, however, has much less force. The only reason that we don’t, after a road incident, demand detailed cognitive-state accounting from human drivers is because we cannot. If we could, we would, and we’d be right to do so. The ‘inspectability’ of ADS does not create an unfair burden on ADS, but reveals an unfair burden that regulators have always had to carry, for lack of any way to shed it. The important distinction is between post-incident inspection and a standing requirement to justify every decision in advance. Regulators should be explicit that they insist on the former, not the latter.

The fourth problem is a concrete human cost to raising the benchmark, and it is the problem I find hardest to dismiss. Every kilometer not driven by an AV that is demonstrably safer than the average human is a kilometer driven by a human who might be impaired, distracted, or exhausted. Elevating the standard from ‘better than average’ to ‘comparable to a professional driver’ is not a neutral move. It is a choice to delay deployment in exchange for a higher standard of care around vulnerable road users. That trade-off may be worth making, but it’s one that critics of driving automation treat as costless, and it isn’t.

“Person Holding White Smartphone Inside Vehicle”, Roman Pohorecki

This argument risks proving too much. It is true that every kilometer not driven by an ADS that is safer than the average human is a kilometer driven by a human who may be impaired, distracted, or exhausted. But an ADS that meets the Professional standard also displaces drunk and distracted drivers; the only difference is that it further exercises heightened caution in places where that is necessary. The foregone-safety argument would justify deploying any system that clears the Average bar, regardless of how it behaves around children (or other vulnerable road users). Few people would accept that trade-off once stated plainly; no regulator that I know of would.

This leaves us in an uncomfortable place. The Average benchmark is inadequate, but the Professional benchmark is a work in progress. We must resist the temptation to resolve the tension by choosing one and ignoring the other.

What Survives

I can see a workable path forward.

Firstly, Waymo and others must meet bright-line requirements for the most legible high-risk contexts: these might include school zones during operating hours, active construction sites, or areas with foreseeable heavy pedestrian activity, for example streets outside a sports arena right before and after a match. In environments like these, the cues are obvious and can be specified in advance. Requiring heightened caution in these settings is no different than requiring an ADS to obey speed limits.

Secondly, for everything else, we should insist our regulators not only impose a full-disclosure regime, but commit explicitly in advance that bad outcomes do not automatically imply fault. The point of disclosure is not to justify punishment, but to make it possible to determine whether an ADS acted appropriately despite an incident. The goal is to ensure that the post-incident conversation includes what the ADS perceived and how it responded, not merely how fast it braked.

A child was struck by a Waymo near a school on a Friday morning during drop-off, and the company’s response was that it hit her less hard than someone else might have. So was this a success, or a failure? The answer is: it depends on the standard we apply.

That answer in turn points to a problem that will not resolve itself. I hope the industry and regulators work together to build a defensible Professional standard, which specifies where heightened caution is required and how it should be demonstrated. I fear that, if they do not, regulators will determine that standard themselves after a more serious crash, in worse circumstances and in a less-forgiving mood.

Respect to Grant Mulligan for feedback on earlier drafts.