At Last, Hydrofoils

The new geography of urban water transit

The Navier N30 looks deceptively ordinary on land, like a surprisingly-oversized luxury day boat. The magic reveals itself when you see what’s underneath. Three carbon-fiber wings extend below the hull, each carefully shaped to generate lift as water flows over them. At speed, these foils will lift the entire six-passenger vessel four feet above the water’s surface; the boat seems to be flying.

The Navier N30; image courtesy of Navier

Understanding what the N30 represents made me believe that urban water transit, a category I’d previously dismissed as impractical, might finally become real.

To be clear, hydrofoils like the N30 are not a replacement for buses and trains; Navier isn’t building mass transit.1 A six-passenger hydrofoil will never compete with a subway car. But deploy enough hydrofoils, running frequently between multiple points, and you create something valuable: premium ferries that offer speed and comfort impossible with conventional boats, serving routes where water creates geometric shortcuts that roads can’t match. They could improve on the water taxi so much as to create something new, adding a genuinely novel category of trip to a city’s transport network.

This is not a new idea, but one that some people have been proposing in vain for more than a century. Hydrofoiling boats are an old technology, first proposed in the late 19th century and first successfully demonstrated by Enrico Forlanini in 1906. But for the most part they’ve only ever been toys, or fads, never reaching full-scale deployment in the West. Has anything changed?

Navier, a Bay-Area startup, thinks it has. During the Progress Conference in October 2025, founder and CEO Sampriti Bhattacharyya and her engineering team invited me and other attendees to visit their production facility in Alameda, where I got to inspect the N30 up close.2 It’s an impressive machine, and Navier is working to commercialize it at scale. What makes them believe they can succeed where Boeing and others failed? To find out, in November 2025 I interviewed Bhattacharyya.

From her, I learned that three technological convergences—in control systems, batteries, and materials—have shifted hydrofoil economics from insupportable to viable. If Navier’s view of the situation is correct, and the company succeeds in making hydrofoils readily available, its success will have implications for the world’s navies, its pleasure craft, and more… but especially for what interests us particularly at Changing Lanes, namely improving urban transport.

So: under what real-world conditions will modern hydrofoil technology move the needle on urban transport? And where will it never work, no matter how good the technology becomes?

Once, a Toy or a Sideshow

First: what is a hydrofoil, anyway?

Put simply, hydrofoils are boats that generate lift to get the hull out of the water. Like an aircraft wing, a hydrofoil uses a curved upper surface and a flatter lower surface. As the boat accelerates, the boat deploys these foils on posts beneath the hull. As water flows over the foil, the curve forces water traveling over the top to move faster than water flowing underneath. This creates a pressure differential—lower pressure above, higher pressure below—that generates upward force. It’s Bernoulli’s principle, the same mechanism that keeps airplanes aloft, but operating in water, a medium 800 times denser than air.

Lift matters because it decreases resistance. A conventional boat pushes through water, and the resistance it encounters increases exponentially with speed. (Specifically: drag scales roughly with the cube of velocity, meaning that to double your speed you need eight times the power to overcome resistance.) This is why fast powerboats are so fuel-inefficient: they’re fighting enormous drag forces as they plow through water at high speed. But lift the hull out of the water and the equation changes dramatically. The Navier N30, once on foils, keeps only the thin wings and drive pods submerged. In motion, as little as five percent of the hull’s surface area is in contact with water.

That’s the key to hydrofoil efficiency: at speed, you’re no longer dragging a hull through water, but instead supporting the boat’s weight with minimal submerged surface. The hull flies above the water, slicing through rather than plowing. This drag reduction translates directly into energy efficiency and range. A conventional electric boat traveling at 30 knots might use 200 kilowatt-hours to cover 40 nautical miles; the N30, foiling at the same speed, uses about 40 kilowatt-hours for the same distance.

Lift has other gifts to offer besides efficient operation. A traditional boat’s stability comes from buoyancy; the boat remains upright because of the shape of its hull and the distribution of its weight. Conversely, a hydrofoil’s stability comes from its control system. Stipulating that the struts are longer than the waves are tall, the hull rides above the surface and doesn’t feel any chop (i.e., the short or ‘choppy’ waves kicked up by wind). The N30’s six-foot struts keep the hull four feet above waves; in three-foot chop, passengers feel almost nothing.

The principles were grasped early. Just over a decade after the first hydrofoil was built, Alexander Graham Bell—yes, the inventor of the telephone—set water-speed records with hydrofoils in 1919; those records would stand for decades. That sounds impressive, a testament to Bell’s genius, but a moment’s thought reveals the opposite. The fact the records lasted so long is a bad thing, Perversely, it tells us hydrofoil was a dead-end technology. (We’ll get to why that was the case presently.)

Through the mid-20th century, hydrofoils were little more than a curiosity: the Soviet Union operated large fleets of riverine hydrofoils, and the U.S. Navy experimented with patrol craft, but none achieved sustained commercial use. The most serious commercial attempt came from Boeing in the 1970s and 1980s. The aerospace giant built its Jetfoil series of passenger hydrofoils that could carry up to 400 passengers at 45 knots. These were actual commercial vessels operating routes in Japan and Hong Kong. Boeing built about 30 of them, before killing the program entirely.

Why mothball the Jetfoils? Because they were expensive to operate and even more expensive to maintain. The control systems required to keep a hydrofoil stable, constantly adjusting foil angles to compensate for waves, wind, and weight distribution, were built with cutting-edge technology for the time: vacuum tubes and early computers. It was a bravura effort, but doomed:

The hulls were aluminum (lighter than the fiberglass common in smaller boats, but still heavy)

The weight of the hull and the gasoline engine meant immense fuel costs, too expensive with post-Oil-Shock gasoline prices

The control system was complex and prone to failure

Foils and actuators required constant calibration

Saltwater exposure corroded the foils and other moving parts

The analogue electronics of the era drifted, requiring intensive, expensive dockside engineering hours for every operating day

It didn’t take long for Boeing to accept that the economics didn’t work. By the 1990s, the firm had exited the hydrofoil business entirely.

That’s the pattern: hydrofoils are discovered or rediscovered as an exciting technology, someone builds a few, and then the project quietly shuts down when operational costs became clear. The physics works well but the economics don’t.

The 2020s Convergence

What’s changed is the convergence of three technological shifts. As Bhattacharyya explained when I asked what’s different from Boeing’s era: “Three things really change the dynamics from the technology perspective: cheaper, faster computing and sensing, batteries, and scalable manufacturing.” We can see all three in Navier’s N30.

The first is cheap, fast, reliable computing and sensing. Boeing’s Jetfoils failed partly because, absent these capabilities, active control was prohibitively expensive. By active control, I mean the complicated series of frequent, precise moves necessary to keep the hydrofoil steady and on course in moving water. Today, active control is cheap, thanks to the smartphone revolution. The sensors that stabilize your smartphone’s camera—accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers—can stabilize a hydrofoil. It’s the same tech stack that enables drones, robotaxis, and other automated vehicles: commodity parts manufactured by the millions, no longer exotic but off-the-shelf.3 They’re available at low cost while being more accurate and reliable than anything available in the 1970s.

The second is battery technology, another gift of the smartphone revolution. Electric motors equipped with high-capacity batteries are lighter, cheaper, and cost less to ‘fill up’ than a gasoline engine. Electric drivetrains are also mechanically simpler, meaning less maintenance, no oil changes, no heavy transmission to support; but the real edge is in cost of fuel. Given that hydrofoiling itself is dramatically energy-efficient compared to traditional hull-in-water boat travel, an electric hydrofoil offers immense savings on operating costs. Navier claims their vessels use 90 percent less energy to run than a comparable conventional boat (30 cents per mile for electricity versus several dollars for gasoline). And while today’s batteries do impose range limits, urban water-transit distances are short: San Francisco to Oakland is six miles, for instance, while Manhattan to Brooklyn is merely two.

The third is scalable carbon-fiber manufacturing. Hydrofoils only work if the boat is light enough for the wings to generate sufficient lift. Traditional hydrofoils used heavy fiberglass hulls due to lack of anything better. But today we do have better: carbon-fiber hulls weigh one-third as much as fiberglass for the same strength. There was a time when carbon fiber was exotic aerospace material, but thanks to modern manufacturing, it’s now affordable for boat-sized structures. As Bhattacharyya notes, the weight difference is dramatic: “If you think about a 30-foot fibreglass boat, it is like three times the weight of what this boat weighs, which makes it easier to lift with the foils.” To be clear: the lighter hull does not reduce drag directly, but it does change the system’s operating point: a lighter vessel can lift off at lower speeds and with smaller foils, reducing wetted surface area and the power required to reach and sustain flight. In practice, this translates into higher efficiency and longer range.

Each of these factors alone would have helped hydrofoils improve, but not enough to be viable, one imagines. But all three converging at roughly the same time means that hydrofoils, previously a toy or curiosity or white elephant, are now competitive with traditional watercraft. The N30 is a capable machine: 30 knots top speed, up to 75 nautical miles of range on a 114 kWh battery, and requires less than an hour to recharge with a fast charger, and all for a base price of $850,000 USD (comparable to a high-end luxury boat).

Nor is that all. Navier is also poised to introduce full vehicle automation, meaning that their watercraft could be the Waymo of the water.

Navier’s boats already feature automated docking, waypoint following, collision detection via radar/cameras/AIS, 360-degree camera coverage, and cloud diagnostics. These are valuable enough on their own: they keep the vehicle even more stable in the water than older hydrofoils, reduce the pilot’s workload, and, critically, allow the boat to dock itself, the trickiest, slowest, and most complex maneuver a watercraft must undertake. As technology proves itself and regulations evolve, full automated navigation will become possible, offering the same potential that robotaxis do: cheap, fast, reliable, safe travel, available 24/7.

Bhattacharyya frames the value proposition around what she calls “the 3 Cs”, namely cost, convenience, and comfort.

Cost (savings) come from hydrofoil efficiency

Convenience comes from integration with existing infrastructure. Unlike ferries, which require specialized terminals costing tens of millions of dollars and decades for permitting approval, the N30 can use any existing marina or dock. “You can take your car to the marina, jump onto a hydrofoiling vessel, and all you’re looking at is: how much time from point A to B”, and what you’ll have to pay for the trip

Comfort may sound like a mere nice-to-have, but it is arguably the most important item on this list; it is what makes small-boat transit possible at all

That last claim needs explication. In two-foot waves, a conventional boat (with what mariners call a ‘planing hull’) subjects passengers to repeated impacts exceeding 1.5g; that's brutal enough to cause seasickness on a single trip and, for regular commuters, risks genuine injury, while guaranteeing an unpleasant time. No amount of cost reduction would make a trip like that viable as transit. Conversely, on foils, vertical acceleration drops below 0.2g. This is a step-change: the ride becomes smooth enough to work on a laptop, hold a conversation, or simply arrive without needing to recover. As Bhattacharya put it, “There's no loud engine noise. You can actually have a conversation.” The increase in comfort that hydrofoils offer crosses the threshold from non-viable to viable.

That’s the future that Navier and its competitors are aiming for. Let’s stipulate that they can make it happen, and can build automated hydrofoils at scale. Where should these craft be deployed?

Where Hydrofoils Will Work

Navier, like all startups, has big dreams, and I applaud their verve.

But as an outside observer, I’m less sanguine than they are that this is a universal technology. In my view, most coastal cities are poor candidates for hydrofoil transit, and no amount of technological improvement changes that, because the geography is fundamentally inappropriate. Viable hydrofoil markets need three conditions simultaneously, and most places fail on at least one.

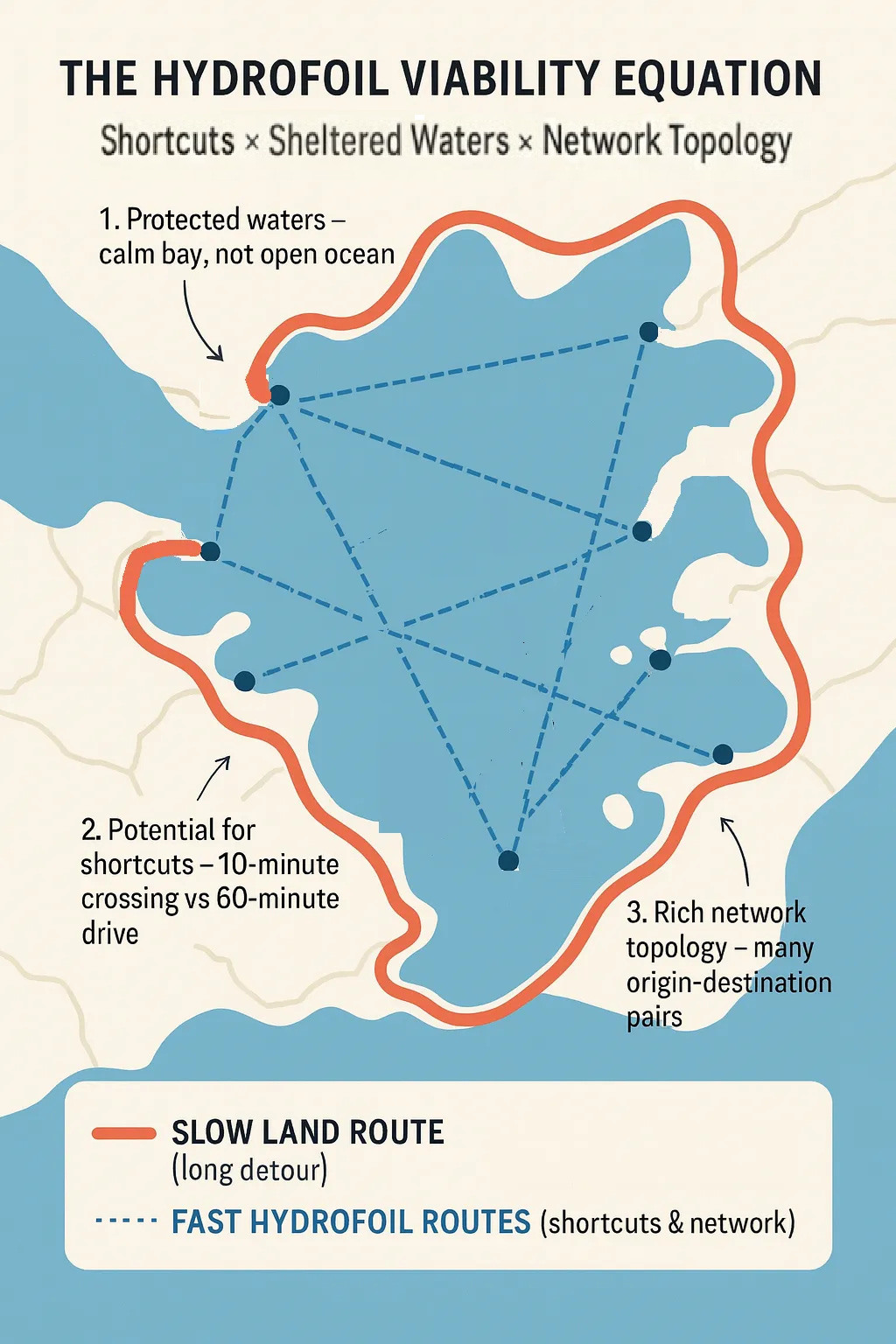

Put another way: the hydrofoil equation is potential for shortcuts × amount of sheltered waters × complexity of network topology. If any of these factors is zero, the use case is zero.

Let’s take those factors in turn.

The first is the potential for shortcuts. A city’s waterfront needs to offer shortcuts that roads can’t match. If your coastline is linear, with water running parallel to roads and rail, boats don’t save meaningful time. Chicago’s lakefront is an obvious example: yes, Lake Michigan is right there, but the lakeshore follows the same north-south line as Lake Shore Drive and the Red Line. The water doesn’t create new opportunities, but only duplicates an axis that already has good transport options.

What you want is non-linear water geography: bays, harbours, straits, or complex coastlines where water creates triangulation opportunities. The obvious example here is San Francisco Bay, which is indeed where Navier has begun to offer water-shuttle service. Going from Oakland to San Francisco by car means driving across the bay via the highly-congested Bay Bridge, a trip of 18 kilometers and who knows how much delay. But traveling directly across the water, one can make the trip in a 13-kilometer, straight-line, uncongested and predictable trip. The bay’s contours give water travel a geometric advantage that roads can’t replicate.

The second is sheltered waters. Hydrofoils handle chop better than traditional small boats—their active stabilization keeps the hull above waves rather than slamming through them—but they still need protection from open-ocean swells. Bays, harbours, and coastal waters work; the open Caribbean does not.4 San Francisco Bay, classified by the Coast Guard as “partially protected,” sees regular three-to-five-foot chop, conditions that would make passengers on a conventional small boat miserable but that the N30 handles comfortably.

The third is multiple origin-destination pairs. A single point-to-point route—mainland to island—is better served by a conventional large ferry. Big ferries have terrible economics for on-demand service and multiple routes, but for a single fixed route with predictable demand, they can’t be beat, because with limited trips and a simple schedule they can always clear the market for trips. Conversely, ferries work poorly, and hydrofoils win, when you have complex network topology: multiple origins and destinations, such that travel demand is a kaleidoscope of combinations. In cases like that, on-demand small boats with short headways provide more value than a big ferry on a fixed schedule.

These three conditions must occur together; fail on any one and hydrofoils probably don’t make economic sense.

There’s a fourth factor worth acknowledging: time certainty. Water doesn’t congest the way roads do. A hydrofoil trip takes the same twenty minutes at rush hour as at midnight; a car trip through bridge traffic might take thirty minutes or ninety, depending on the day. That predictability has real value, particularly for high-income commuters whose time costs are significant.5

But I’m skeptical that time certainty alone—without geometric shortcuts—creates genuine urban transit. Transit serves masses of people across many origins and destinations; it requires accessible infrastructure and price points that attract riders beyond the wealthy. A hydrofoil service competing on comfort and predictability with a car trip of similar duration is a premium product, not mass transit. It’s a better limousine, not a better bus. In corridors where water also saves distance, the economics shift: you get time certainty plus time savings, a combination strong enough to attract ridership beyond the luxury segment. That’s why I weight geometric shortcuts heavily in my framework; not because time certainty doesn’t matter, but because without distance savings, you’re building a niche service rather than changing how a city moves.

Taking all of these factors together, we can immediately see that San Francisco Bay is the gold standard. Non-linear geography? Absolutely; crossing the bay saves enormous distances. Sheltered waters? Yes; it’s a bay, not open ocean. Wave conditions get rough during storms, but most days the Bay is navigable for small boats. Multiple origin-destination pairs? Oakland, San Francisco, Alameda, Berkeley, Sausalito, Tiburon, and more make for dozens of potential routes creating a genuine network. If hydrofoils work anywhere, they work here.

Call San Francisco Bay a ‘Tier 1 market’ because it achieves all three criteria. There are many other big markets that fit this pattern, notably including New York Harbour, Puget Sound, Stockholm, and Hong Kong (and perhaps Tokyo Bay, though it’s less of a slam-dunk). All have non-linear geography, sheltered waters, and enormous populations creating demand for multiple route pairs. Hong Kong especially demonstrates the potential: Victoria Harbour’s sheltered waters and dense island-to-island network make it ideal hydrofoil territory, and indeed it’s one of the few places where old-school hydrofoils operate. These are Tier 1 markets, where conditions clearly align.

Tier 2 includes strong candidates with slightly less ideal conditions: Chesapeake Bay, Boston Harbour, Vancouver, and Singapore. These have good geography and reasonable protection but either limited network density or occasional weather constraints that reduce reliability below Tier 1 standards.

Tier 3 is speculative. South Florida and Miami demonstrate the challenge: Biscayne Bay looks promising on a map, but weather volatility might create frequent interruptions; Tampa Bay faces similar issues.6 There may be many European, Chinese, and Australian harbours where it would work, but I’m insufficiently expert to make confident predictions.

What is clear to me, at least, is that hydrofoil transit isn’t going to reshape coastal urbanism broadly.

To be equally clear, Navier disagrees with me on this point. As far as urban marine transport goes, they see a hundred or more viable markets where I see fifteen to twenty-five. That gap reflects both definitional differences and genuine analytical disagreement. Navier’s count appears to include seasonal resort destinations, island lifelines, and intercity marine corridors that fall outside my focus on year-round, networked urban commuting. It also reflects a different weighting of factors: Navier places more emphasis on time certainty and ride comfort in the absence of large geometric shortcuts, whereas I treat those features as necessary but usually insufficient on their own.

I'm open to the possibility that I am mistaken, but as far as I can tell, it is the case most coastal cities fail on geography, protection, or network topology. But in the 15 to 25 major metropolitan areas globally where all three conditions align, hydrofoils could meaningfully improve transportation; these metros are home to hundreds of millions of people and trillions of dollars of economic activity.

Taken together, the geography test sharply narrows where hydrofoils make sense, which means it’s fair to ask whether today’s technological improvements genuinely change hydrofoil’s viability.

The Hinge Moment

So is this time different? After a century of disappointment, is hydrofoil finally ready for prime time, at least as an urban-transport mode?

I say yes, but with caveats.

The convergence is real. Cheap smartphone sensors have solved the control-system problem that killed Boeing’s Jetfoils. Carbon-fiber manufacturing has scaled enough that lightweight hulls are economically feasible. Battery technology has improved enough that electric propulsion works for urban water-transit distances.

But despite all that, the area where hydrofoils can succeed is bounded. If I’m right, the three-conditions framework—non-linear water geography, sheltered waters, multiple origin-destination pairs—limits viable markets to perhaps 15 to 25 metropolitan areas globally. That’s valuable but not transformative urbanism. Most coastal cities fail on at least one condition, and those conditions can’t be overcome with technology: tech can’t make hydrofoils outcompete cars or trains on linear coastlines, nor conventional ferries on simple, single-route cities. Nor can tech keep hydrofoils from being uncomfortable or unsafe in rough waters.

Even so, this is a technology that can meaningfully improve transportation in specific places with the right geographic and regulatory conditions. That market is large enough for multiple players to succeed if they navigate obstacles competently, and large enough to improve transportation and make life meaningfully better for millions and millions of people. And of course, urban transport is only one of the many uses hydrofoils could, and should, be put to; it’s only one of the problems Navier has set out to solve.

I can imagine riding across San Francisco Bay—serenely gliding above the water while moving at a speedy thirty knots—watching the city skyline approach in minutes rather than the hour-plus it would take driving around via bridge. That experience, multiplied across the handful of metros where geography enables it, will be genuine progress in urban transport. Succeeding in particular circumstances for specific use cases is still success.

For the first time in a century, technology exists to unlock marine transit in major global cities. If things go right, progress will happen in real time before our eyes. It’s an exciting time, and I look forward to seeing where Navier goes from here.

Respect to Grant Mulligan and Venkatesh V Ranjan for feedback on earlier drafts.

Navier characterizes the N30 as the first demonstration vessel of a broader “generalized marine vessel platform” or GMVP, developed for multiple applications, including defense and commercial maritime uses that are beyond our remit at Changing Lanes. The company argues that hydrofoiling enables a combination of low operating cost, long electric range at speed, and rough-water capability—attributes that have historically traded off against one another in marine design. On this account, the N30 is not itself a mass-transit vehicle, but a proof point for a platform Navier believes could eventually support a variety of new activities, including (but not limited to) high-frequency urban water transit at scale.

Tomás Pueyo, whose work on urban geography I admire, also attended this workshop and subsequently published his own analysis of water taxis as urban infrastructure.

Hydrofoils come in two varieties. Passive foils use fixed V-shaped wings that provide some natural stability but can’t actively respond to waves. Active foils, like those on the N30, use computer-controlled flaps that adjust 30 to 50 times per second, maintaining altitude to within two centimetres. It is the smartphone revolution that has created the potential for active hydrofoiling at scale.

Navier’s current limit is four-and-a-half-feet waves, which they tell me is not a hard limit. This may put the open waters of the Caribbean out of play, but Navier believes their vessels will handle most coastal cities, outside of storm conditions.

Though at scale it’s easy to imagine that docking infrastructure could become congested even if the waters themselves aren’t. But if docking can be automated, this problem fades; it would be straightforward for congested ports to scale facilities up to meet peak demand.

Navier thinks the N30 is up to the challenge of Biscayne Bay. I’m unsure; I look forward to seeing the results of deployment. I’d be happy to be proven wrong!

I enjoyed blasting down the Neva River in St. Petersburg on Russia's Flash Gordon-esque hydrofoil ferries back in 1990...a real trip. And I immediately think of Brisbane, Australia which has a very popular and effective ferry component to their transit network, consisting of both high-speed express catamarans going up and downstream, and a bunch of little point-to-point cross-river ferries to deal with the serpentine Brisbane River. Other Aussie centres (Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth) may also have potential. And there is the perennially doomed Toronto-to-Niagara ferry concept, but those water conditions likely fall outside of the parameters of this concept.