Rail Models, Piracy, DoorDash, and Jack Black

Off-Ramps for 15 May 2025

Welcome to Off-Ramps! Today I’ll highlight four interesting pieces that I think you will enjoy reading. Please enjoy these on your morning commute, or save them for your weekend.

First, though, an announcement.

Changing Lanes on the Road

Next week, on 22 May 2025, I will be in Ottawa attending the ITS Canada conference. There, I’ll be giving a fireside chat with Barrie Kirk of CAVI on the theme Charting Canada's Course in Connected and Automated Vehicles. Drawing upon CAVI’s white paper on the subject, which Barrie and I co-authored, we’ll discuss how Canada can develop and implement a national strategy for driving automation. I hope to see you there!

The UK Is Terrible at Rail Forecasting

Virtually every reopened rail line in the UK has wildly exceeded passenger forecasts—sometimes by a factor of five.

Harry Rushworth's analysis of Britain's surprisingly successful rail reopenings reminds us that transport models should always be assumed to be political tools, not technical ones (hat tip to Lauren Gilbert for the link).

As per Rushworth, upon opening the Northumberland Line hit 250,000 passengers in three months, against an annual forecast of 704,000. The Borders Railway carried three times its projected ridership. The reopened Okehampton branch railway had double the anticipated passengers in its first year. And on and on; the pattern repeats across the UK.

Why is British forecasting so bad? As per Rushworth, these aren't modelling failures; they're modelling features. British transport modelers systematically lowball projections because the political cost of overestimating demand far exceeds the cost of underestimating it; no one wants to be the parent of a ‘boondoggle’ or ‘white elephant’, so it’s better to kill ten likely-good projects to avoid sponsoring one that underperforms.

Rushworth suggests building infrastructure with spare capacity and devolving decisions locally. I wish I could agree, but I can’t.

I am a former transport modeler myself, having built them at different times throughout my career for different interests. I have seen the dynamics Rushworth describes: models where obvious features that would make a project feasible are deliberately excluded on spurious grounds, to ensure the project does not advance. But I’ve also seen models built after projects were approved, as post hoc exercises in justification of decisions already made. So there’s no magical solution here: models can express bias in both directions.

The best solution I can think of is to make them open-source: a model has to be built before a decision is made, and then published, with robust description of assumptions, and partisans for and against encouraged to challenge. Absent this sort of adversarial collaboration, models are not useful decision-making tools; they’re just a club to beat one’s opponents with. We should do better.

21st-Century Piracy

More and more of the United States’ freight system has been hijacked by pirates, and the heist is accelerating. Cargo theft surged 26% from 2023 to 2024, resulting in nearly $455 million USD. That’s reported losses; actual losses likely exceed $1 billion due to underreporting.

You may be thinking these are Sopranos-style operations where truck drivers are held up at gunpoint, or sophisticated nighttime warehouse heists. But they are neither; these are digital crimes. The thieves hack into freight platforms and federal databases to establish briefly-credible identifies as legitimate freight haulers. Then they submit winning bids for shipping contracts, legally pick up cargo, then either vanish entirely or hold shipments hostage until additional ransoms are paid. By the time companies realize they've been duped—often weeks later—the goods are gone. The geographic concentration of thefts around major logistics hubs in California, Texas, and Florida leads one to expect that these are drug traffickers branching into new lines of business.

Ryan Petersen, CEO of logistics giant Flexport, warned about this last summer, talking about a then-wave of such crimes, which had been building since 2022 (hat tip to Zvi Mowshowitz for promoting the thread to attention). As part of a laudable effort to become more efficient, the freight industry rushed to digitize its operations by eliminating human gatekeepers. The need of honest brokers to make many phone calls to many people to set up shipments was doubtless annoying and time-consuming. It turns out, though, that it had the unappreciated benefit of vetting firms as trustworthy. Eliminating those calls created vulnerabilities that criminals are exploiting. Inadvertently, the freight industry invested all of its security in federal carrier databases, the sort that even a middling hacker can abuse.

Flexport's response was to develop ‘CARVE’, an AI-powered system that uses machine learning to identify frauds and bad actors. Petersen and Flexport chose not to return to old-school phone verification, which seems prescient, given the voice-spoofing tools that AI has given us. Petersen says that the freight industry as a whole had better get serious about using digital tools to know who they are working with. I agree with him, but want to make a larger point: there is no escaping AI tools now. If criminals and bad actors are using AI for dark purposes, their would-be victims will take up AI to defend themselves.

AI is now an arms race. Attempts to opt out of using it will only mean you are outcompeted or victimized by those who don’t.

How DoorDash Won

The business school version of why DoorDash won is that they had the right strategy. The Silicon Valley hustle culture version is that they out-executed everyone else. The financial markets version is that they got lucky. The reality is that you can't understand what happened without all three perspectives.

Dan Hockenmaier, Why Did DoorDash Win?

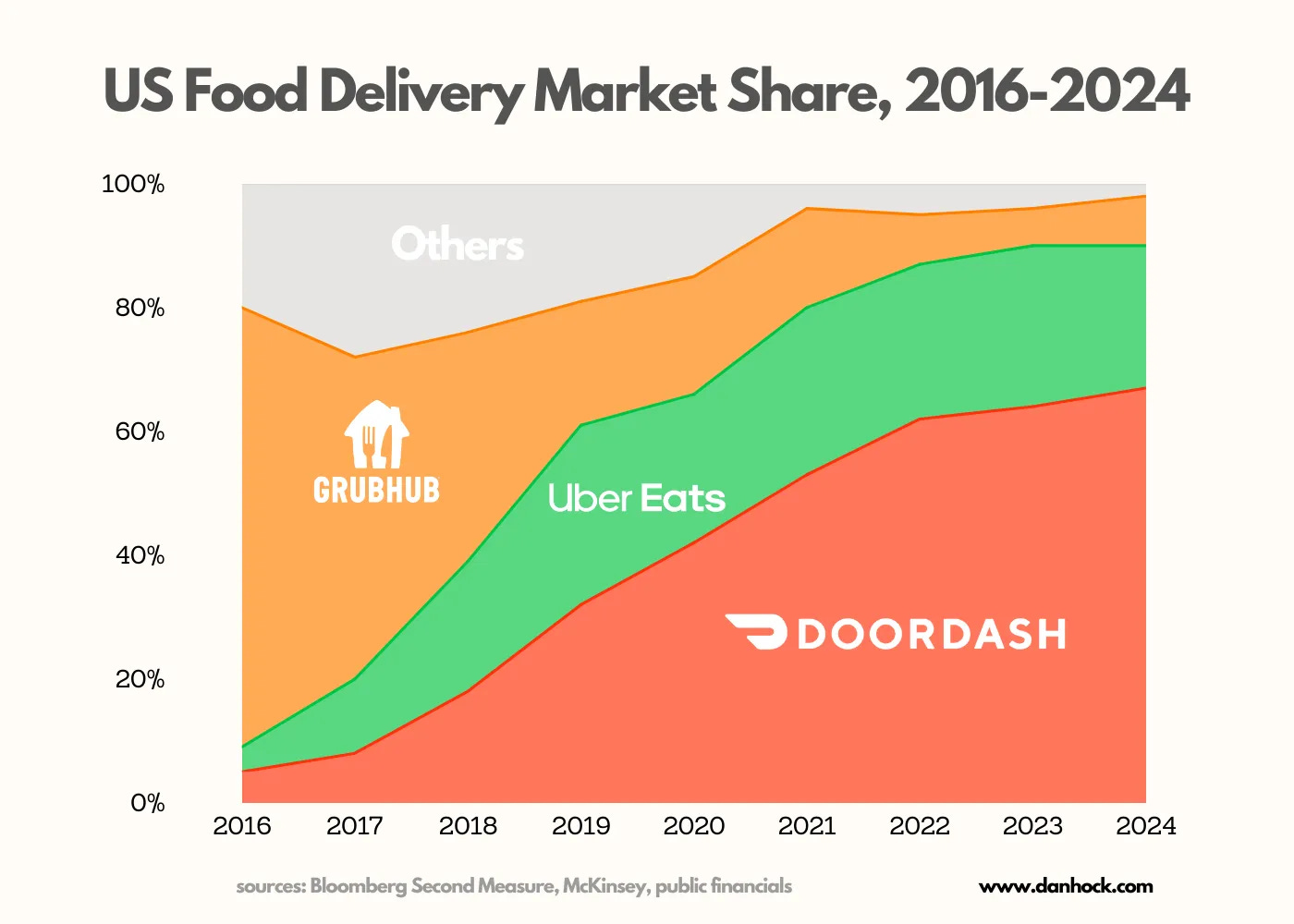

Dan Hockemaier brings the news that the war for food delivery is over, and DoorDash won:

How did they do it?

In a word, they conquered the suburbs, and the rest followed.

Uber and Grubhub, following conventional wisdom about logistics, aimed to win the USA’s dense urban cores, on the theory that density meant more customers and shorter delivery times; they worked to shorten delivery times, to maximize filled orders and to outdo their rival.

Meanwhile, DoorDash went to the suburbs. Yes, the suburbs had low population density, with all of the problems that followed. But suburban customers also had worse alternatives and higher order values. Better still, there was no competition: neither from other delivery companies, nor from alternatives to delivery (no restaurants within walking distance).

So while its competitors obsessed over delivery speed, DoorDash obsessed over restaurant selection. They recognized that as long as food arrived within 40 minutes, customers would be happy, and faster arrival was less enticing than variety of options. So DoorDash made another counterintuitive move, making their service more expensive to offer commission breaks to premium restaurants. The result was a virtuous cycle of better selection, which brought more customers, which attracted more restaurants, which offered better selection.

It’s good to be skilful but better to be lucky. Immediately before the pandemic hit, publicly-traded Grubhub had to satisfy the market and keep costs down, while Uber was distracted by its IPO. DoorDash, still private, had a window and used it, burning a staggering $475 million to capture market share. And when the pandemic hit, ushering in a new age of food-delivery demand, they were on top, and have gone from strength to strength since.

DoorDash’s story is a fun exercise in business strategy analysis, and the delivery angle makes it relevant to Changing Lanes. But I might add that DoorDash has lessons specifically for students of urban mobility. DoorDash won by recognizing that for their customers, there was a speed bar that had to be cleared, but once it was met, customers prioritized getting exactly what they wanted over getting it incrementally faster.

Transit operators face their own tradeoffs between variety and speed; variety of destination rather than cuisine, but the dynamic is the same. On this view, the first priority for operators is minimum speeds and trip-time thresholds; once those are established, there’s more value in expanding coverage than shaving trip times more.

“The Humiliation of the Coward Jack Black”

The reason the zoomers like it, is not some ironic doubly irony joke where they pretend to like a bad movie... The reason they like it is because they resonate with a story about being [captured] by a magical portal that sends you to a fake world you have to escape from.

Egg Report, The "A Minecraft Movie" movie is the most reactionary movie I've ever seen and the future zoomer world order is bright and wonderful

In the past when I’ve included movie reviews into Off-Ramps I found transport fig leaves to cover them. Here I can’t find one but I enjoyed this review so much that I had to bring it in, theme or no theme.

‘Egg Report’ argues that A Minecraft Movie, obviously intended as a corporate IP cash-grab… is that, yes, but is also a cutting Zoomer critique of the Millennial generation. Beneath the irony and commercial chrome, A Minecraft Movie tells the story of Henry, a genuinely creative Zoomer protagonist, who is obliquely pitted against Steve (played by Jack Black), who represents everything hollow about Millennial ‘creativity culture’. Sure, Steve bloviates about how the Minecraft world is a haven for imagination, but, says Egg Report, the movie systematically demolishes that claim. Steve’s creativity amounts to addictive, mindless, “number go up” grinding; joyless repetitive labour packaged as fun.

So the Minecraft world itself isn’t paradise, but a hyper-coloured prison of dopamine hits, a metaphor for the broader Zoomer experience of being “sucked against their will into a rectangular portal”, i.e., thrust from childhood into screen-mediated reality without an intervening step. When Henry unhesitatingly chooses to return to the real world at the film's end, he's rejecting not just Minecraft, but the entire premise that virtual space is a sufficient substitute for in-person community.

On this reading, the movie's villain isn't just the witch Malgosha, the nominal antagonist, but Steve himself, a man-child who's wasted twenty years in digital caves preaching about creativity. If so, that would mean that Jack Black is either deeply committed to the bit, never once winking at the camera to show that he’s in on the joke… or that he’s not in on the joke, and is genuinely oblivious to who the character he’s playing is, making the portrayal all the richer.

I haven’t seen the film, so I can’t comment on whether this interpretation holds up. But that’s beside the point. If Zoomers, the film’s audience, are indeed responding to it in this way, it suggests a generation whose commitments and sophistication are rather different than I had believed.

I am as surprised as you, but I look forward to watching this film when it becomes available to stream.